“Pep used to say that he is the most defensive coach in the world.”

Mikel Arteta, Arsenal’s coach

In the last season of European, or more specifically, English football (2022/2023), we saw a new tactical trend emerge in the two teams competing for the Premier League title. Arsenal and, especially, Manchester City often sent to the pitch four defenders in their starting XI throughout the competitions they participated in. Yes, four defenders. A complete defensive line of center-backs. And this trend has been intensifying in the current season.

The following text not only attempts to explain how this system filled with 1.90m towers operates, but also seeks to understand the motivations behind the chosen path by the world’s most influential coach, Pep Guardiola, and analyze them critically. Let’s go point by point.

1- Questioning

Apart from being impressed by the fact that Guardiola can make a team with a defender as a midfielder play attractive and efficient football, have you ever wondered what’s the real advantage obtained through this choice? What is the intention behind it? What did the coach envision in his plan, and what is the material impact of this on the game?

It is truly intriguing and enchanting to see the system working seamlessly with Akanji orchestrating plays so close to the opponent’s area. For those of us, I believe, who are interested in tactics and consume championships all around the world in not-so-healthy doses, spending hours of the week with our eyes fixed on a screen (or even two), watching game after game, always hoping to see something that surprises us and renews our desire and curiosity for the next one, it is enjoyable to come across something so unusual. “My God, he did it again. The genius has innovated once more.” So, we rush to the football WhatsApp group and Twitter timeline to praise the new tactical mechanism that will revolutionize football.

However, I can’t help but wonder. What does Manchester City gain with Akanji as a midfielder in a 2-3-5 formation? How does Arsenal benefit from having Tomiyasu and Ben White orchestrating plays from the inside in the very same 2-3-5? And finally, how does this sustain itself in a model that, at the high level it is executed, should demand players with the highest technical quality and skills? Center-backs, who are undoubtedly the best in the world and have unparalleled ball-playing abilities, are capable of fulfilling these functions… Well, let’s proceed with the analysis.

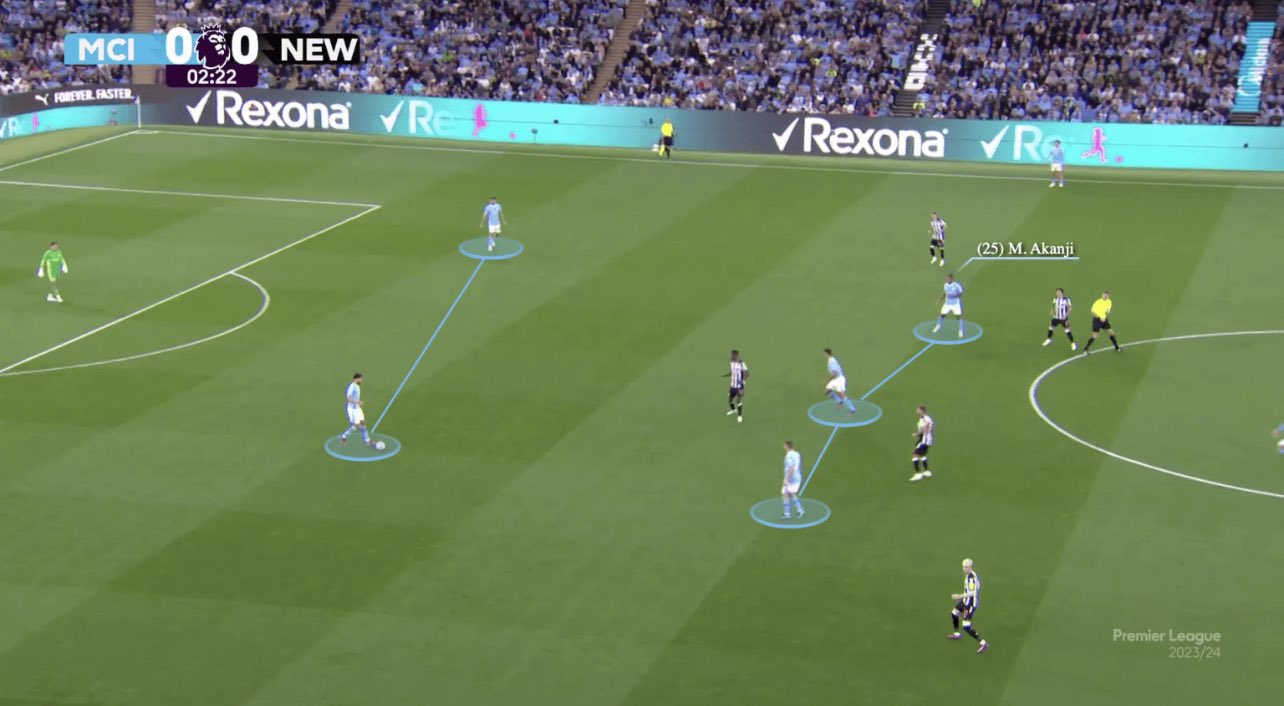

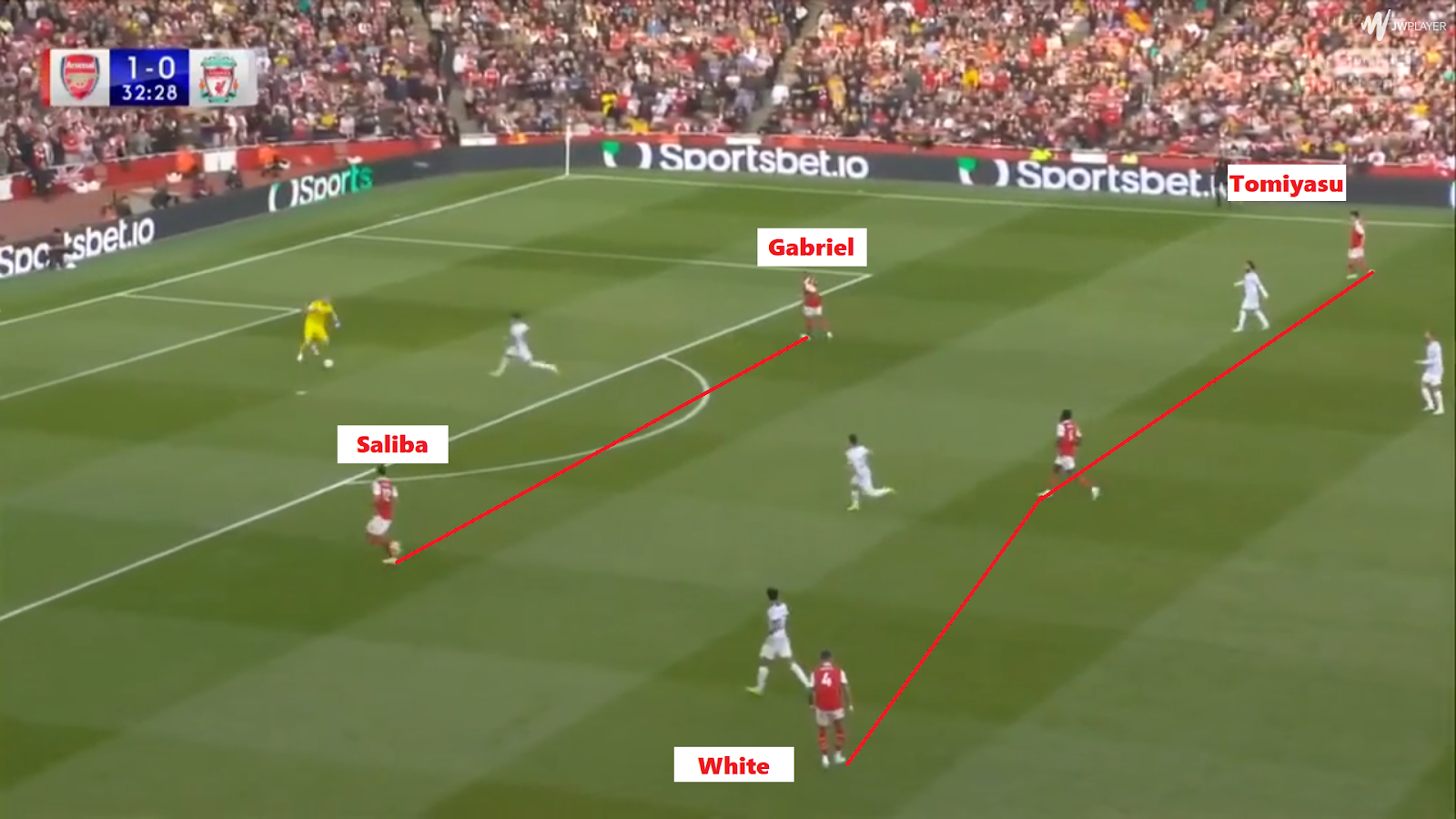

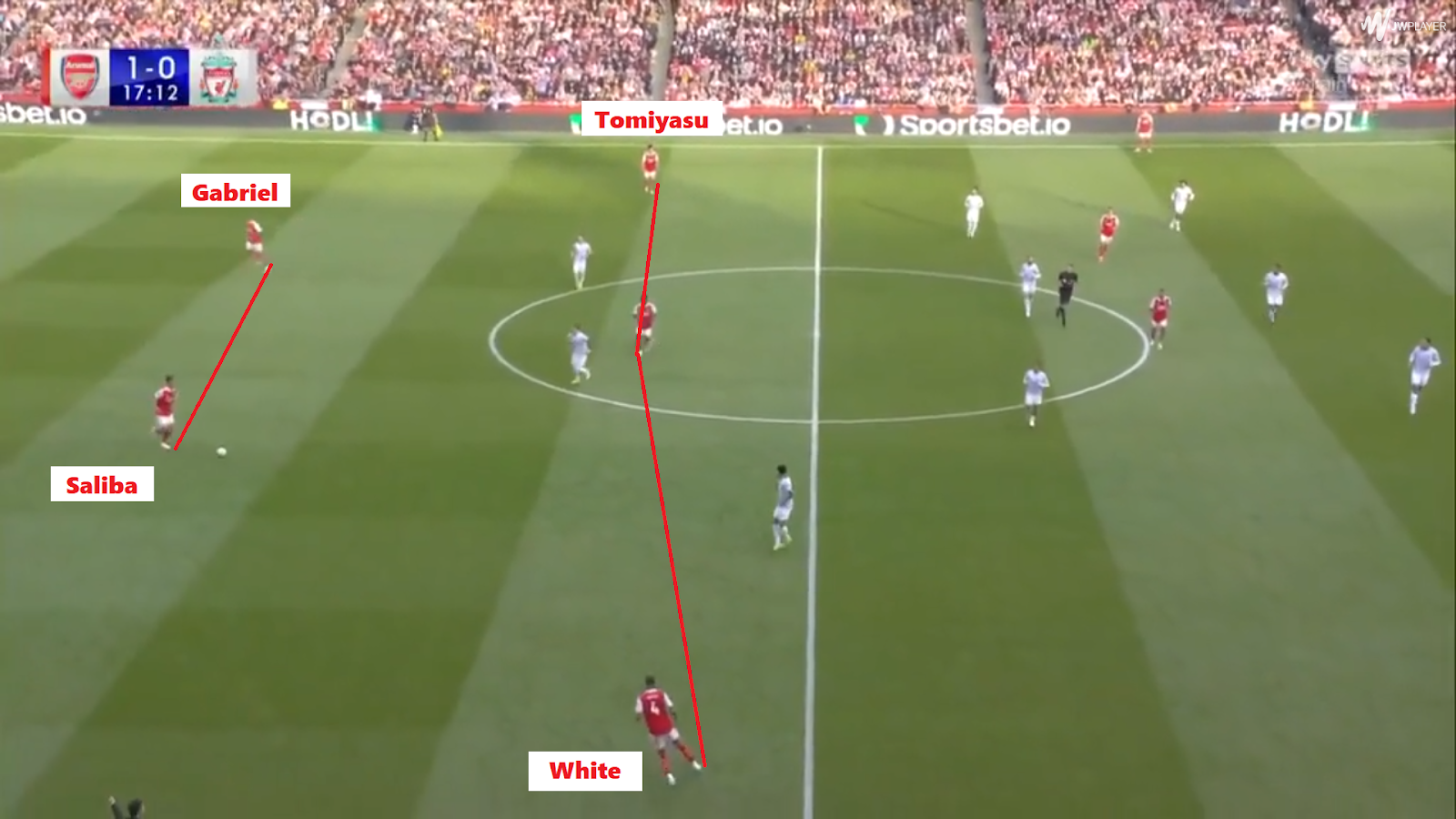

Arsenal’s 4-3-3/2-3-5 formation in this match against Liverpool in October 2022 featured Tomiyasu, Gabriel, Saliba, and White. The long distances, especially in the initial phase of building up, as shown in the photos, caused the “center-back full-backs” to stay wider. However, the playmaking responsibilities continued to rest on 4 center-backs and 1 midfielder, Partey.

2- The Milestone: Manchester City Champions of the UCL with 4 Center-Backs

Starting from the Round of 16 return leg against Leipzig, which City won 7-0, Guardiola fielded 4 center-backs in all the knockout stage matches of the 22/23 Champions League. Regarding the role of Kyle Walker, which I know can cause debate, I would like to anticipate my counter-argument. In the semifinals against Real Madrid, Aké was unavailable due to injury. In his place, the Englishman, unquestionably a natural full-back, played as a right-sided center-back in the 3-2-5 formation. Due to his speed, I believe Walker would have been the choice to contain Vinicius Junior regardless of the Dutchman’s injury. The “what if” doesn’t matter. As mentioned earlier, this is the primary role that Walker has been performing for Manchester City and the English national team for several seasons. Therefore, I consider him a center-back.

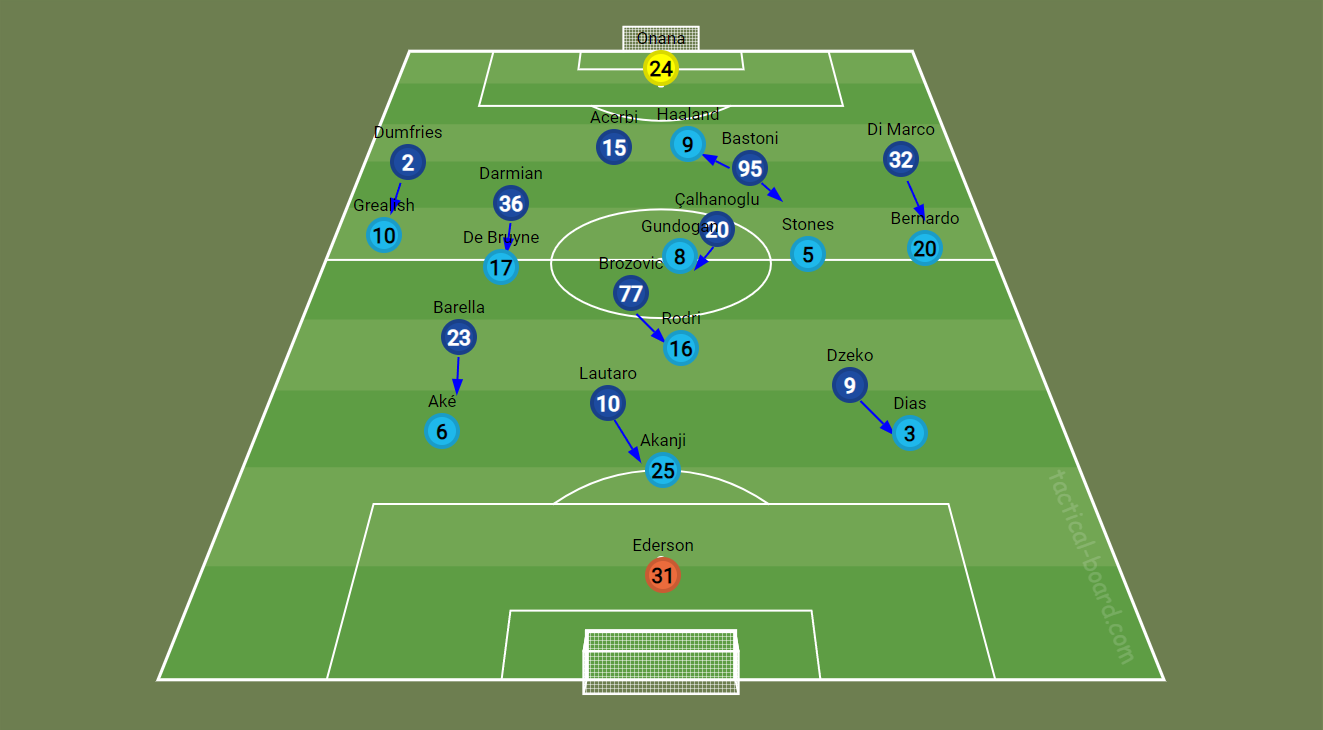

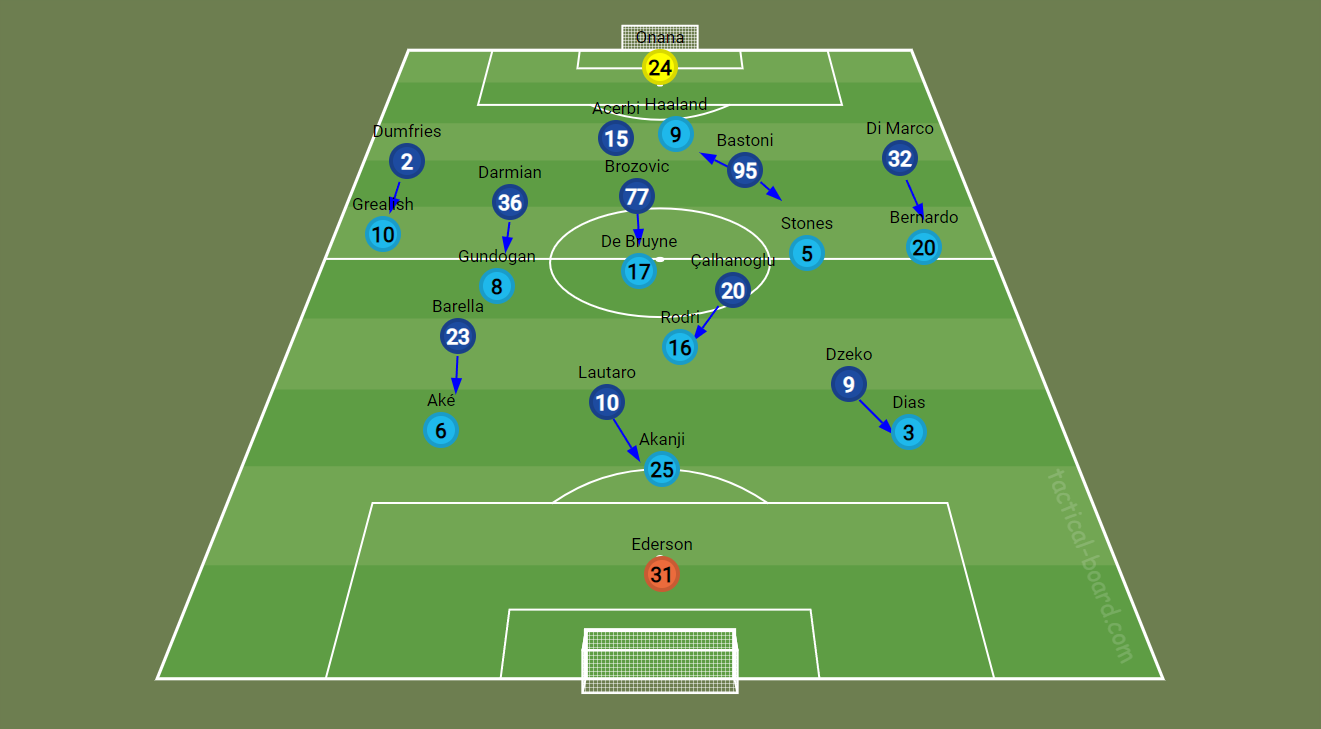

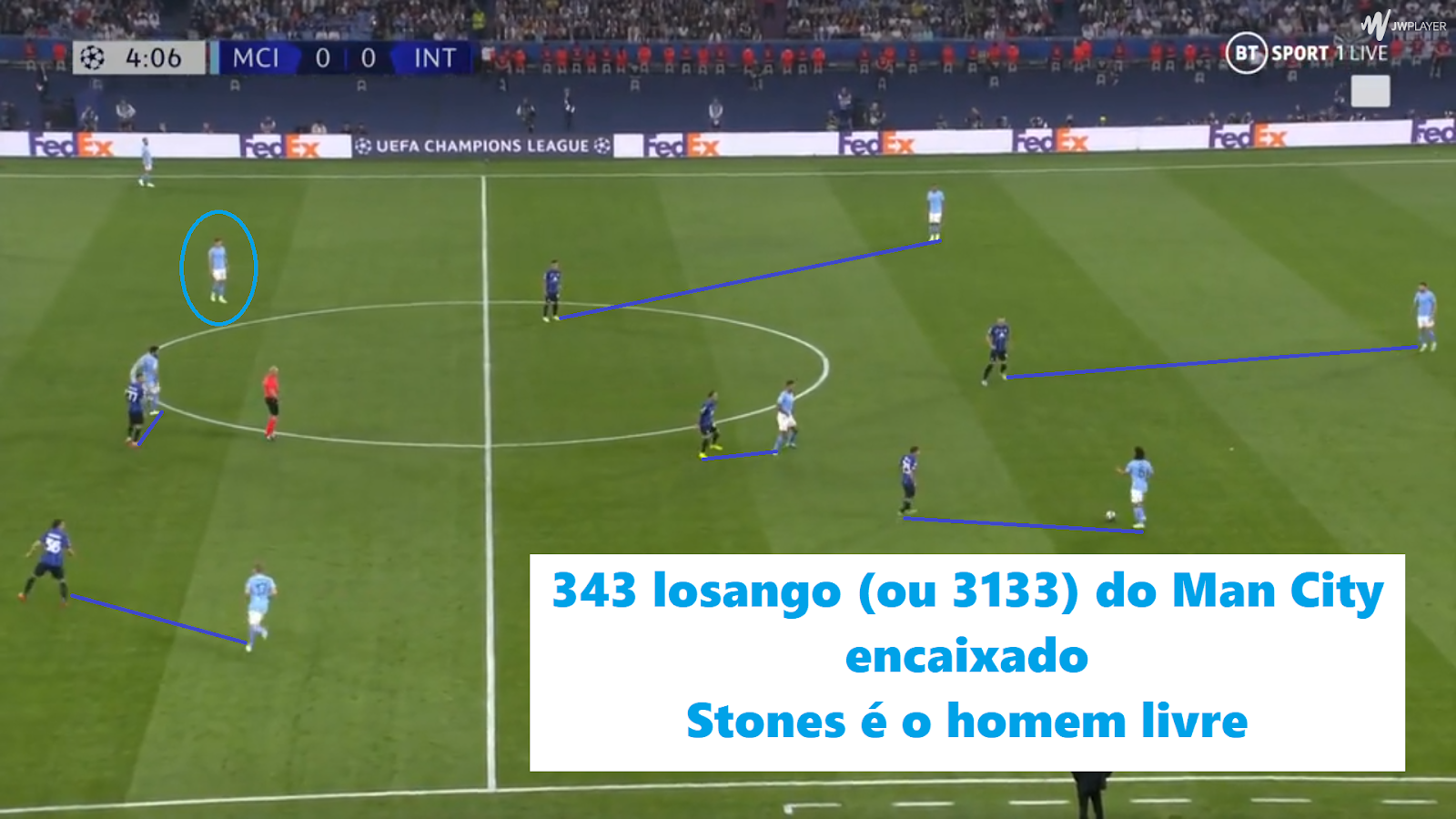

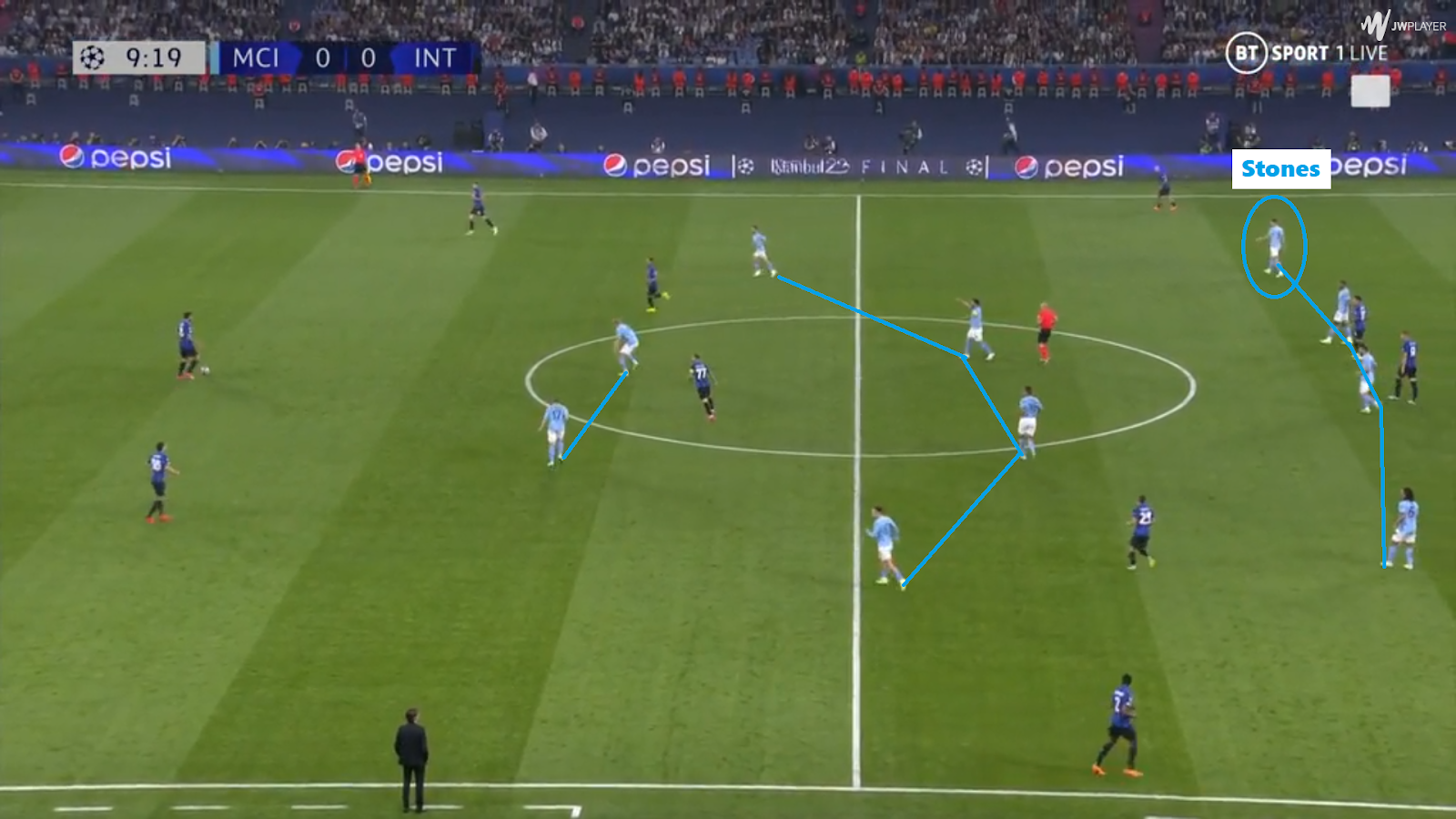

In any case, in the final, it was Nathan Aké who played alongside Rúben Dias, Manuel Akanji, and John Stones. The latter stood out immensely for acting as a true midfielder in Manchester City’s 3-4-3 diamond formation. The match revolved around him because he was the free man in Inter’s defensive system, and that will be the focus of the analysis to follow.

The diagrams summarize how the Nerazzurri’s defensive system worked in relation to the Cityzen’s offensive scheme. Lautaro would press Akanji, Dzeko would run towards Dias, and Barella, being more physical than Çalhanoglu, would go up to Aké, completing the line of defenders. The wing-backs would fit in, with Dimarco marking Bernardo, and Dumfries covering Grealish. This is the simplest part of the model, while the defense and midfield required more adaptations.

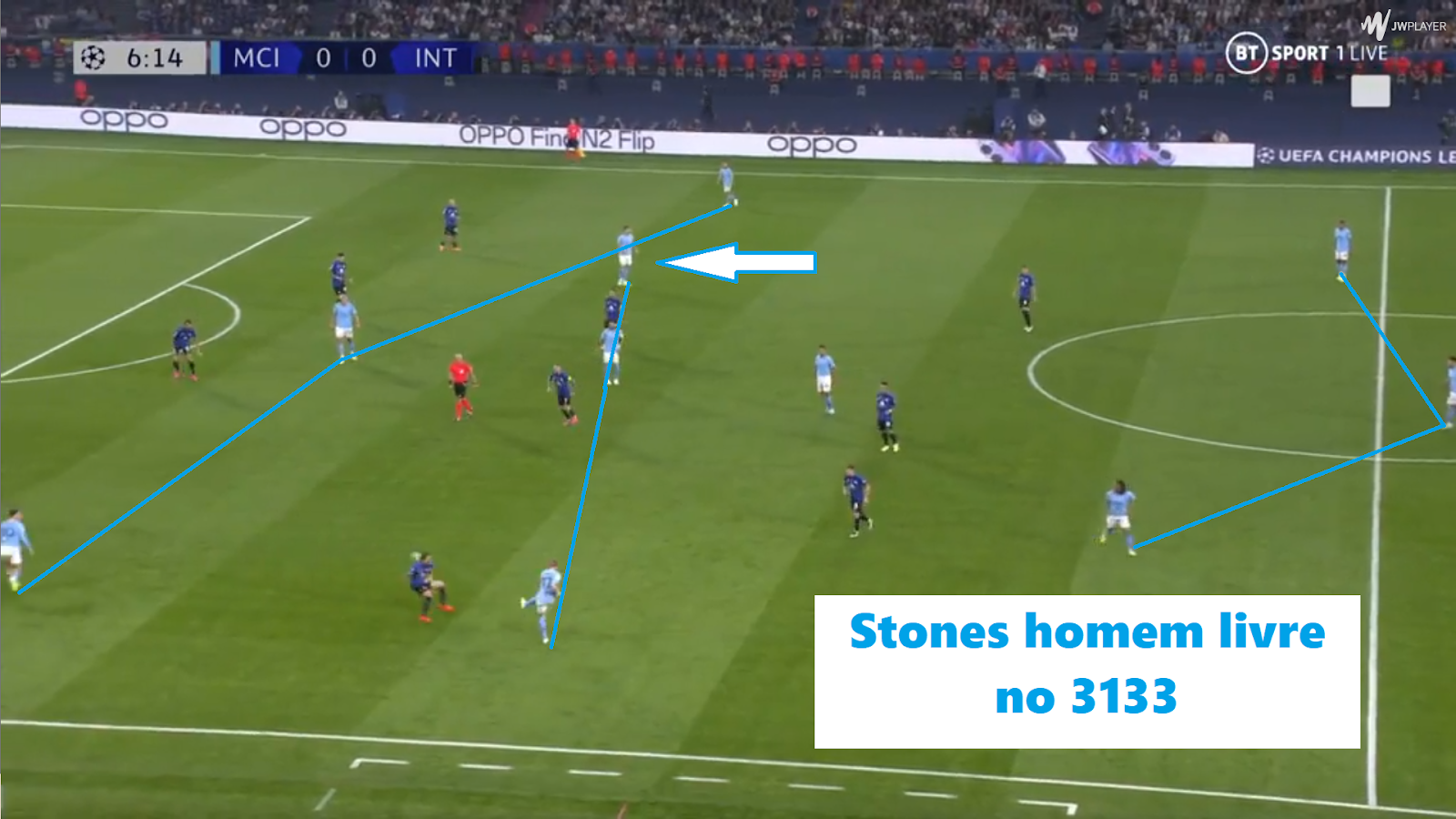

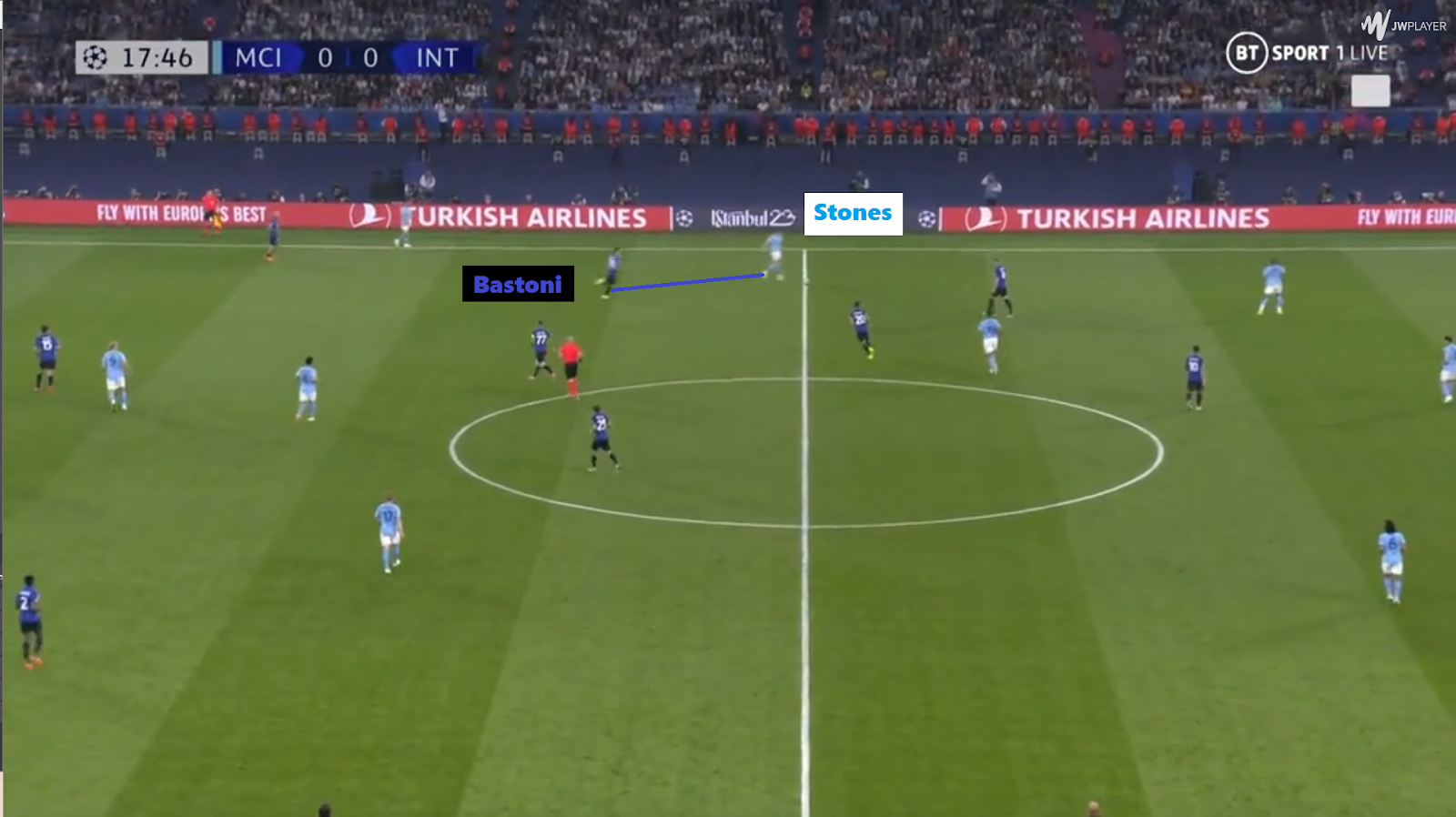

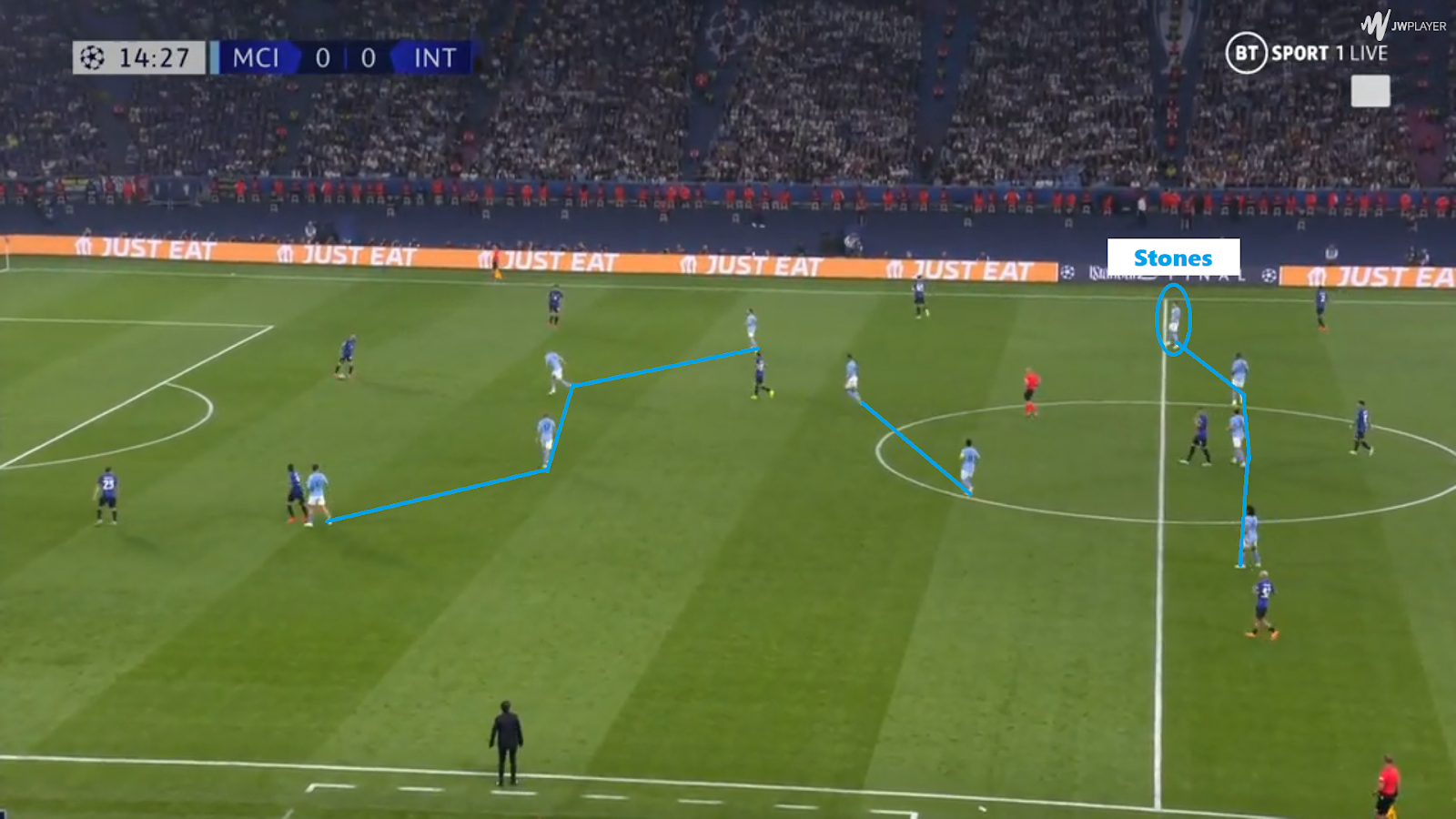

Initially, Brozovic, with his endless energy, would press Rodri high up the pitch, and the Turkish player would mark Gundogan. However, when Gundogan switched positions with De Bruyne or the team’s defensive line dropped deeper, Brozovic would become responsible for the high point of the diamond, with Çalhanoglu marking Rodri. This way, Darmian was tasked with tracking the left-sided midfielder in the diamond, but the same did not apply on the right side. This was because Simone Inzaghi’s idea was to have Acerbi as the ”líbero”, allowing Haaland to always be in a 2×1 situation, with the quick Bastoni constantly on his tail. In other words, Stones was the free man. No Inter player prioritized marking him, making him a constant passing option. This seemed logical since he was a center-back receiving the ball with his back to goal. Bastoni’s role was to share the reference. If he saw that the pass was definitely directed to the Englishman, he would press, and Acerbi would cover him. Otherwise, he would continue marking the android.

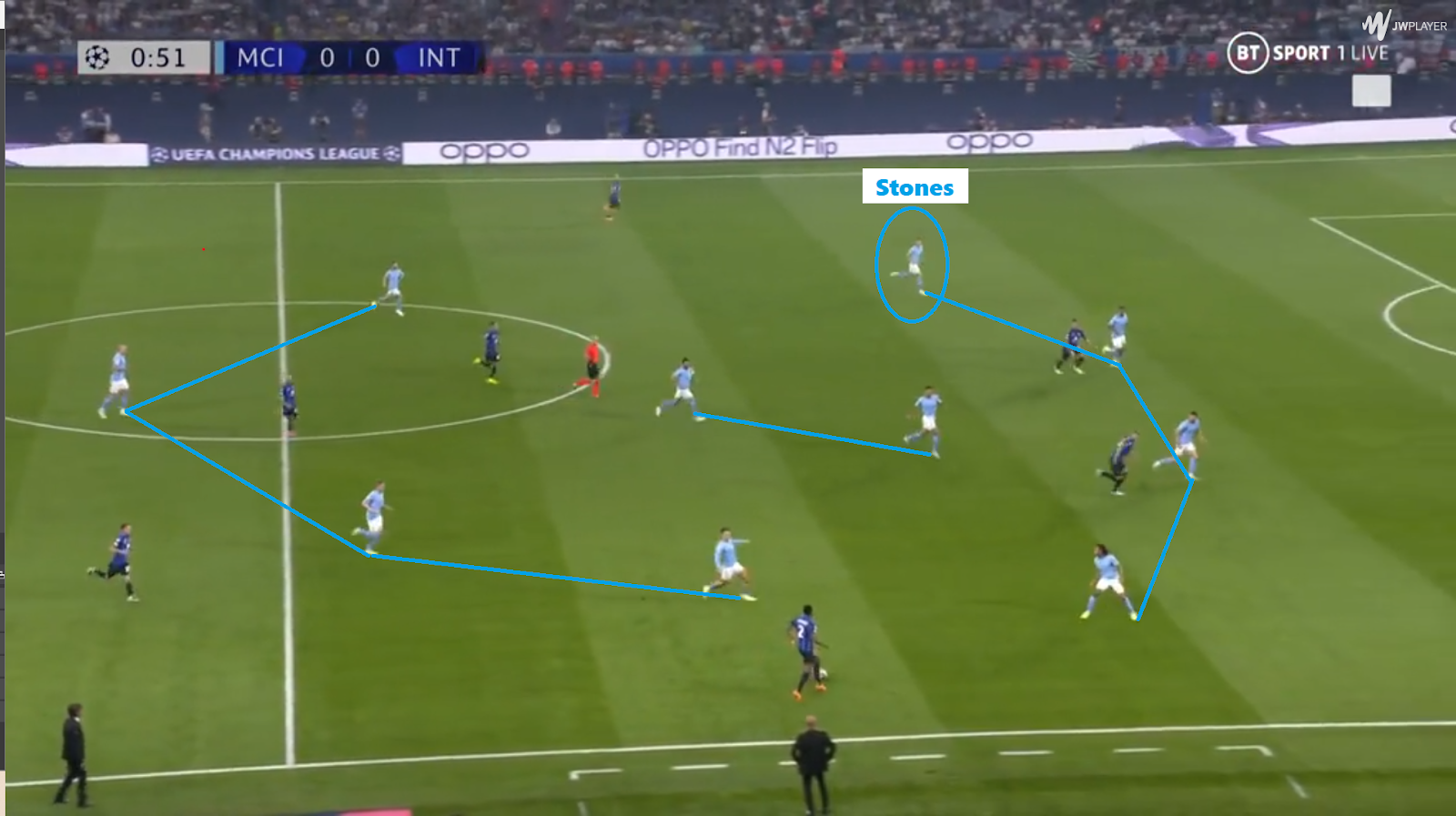

In this play, Stones starts as the right-back in the initial phase of the buildup. Possession develops, the diamond structure takes shape, and Bastoni attempts to press the Englishman. Cleverly, Stones feigns a support run, changes his path, and gets behind the Italian. Acerbi wins the duel against Haaland and disrupts the development of the fourth man’s dynamic.

Finally, as the play unfolds on the left side, Bastoni doesn’t concern himself with Stones. However, as the balance shifts, he begins his press. In this particular play, he pushes the defender backward and forces the ball back to the left side. He may have lost the duel, but the trip was not in vain.Here, Bastoni hints at pressing but realizes that the pass is difficult, and the play will develop on the left side. Therefore, he abandons the chase and returns to the 2×1 against Haaland.

To conclude the offensive phase, a possession where Stones starts by offering support inside, plays with his back to goal, and maintains control for City. Then, he traverses the field with the swing of the play and ends up taking up width on the right. Pay attention to the confusion this causes in Inter’s defensive positioning. Acerbi, as the ”líbero”, initially presses, reverts to the defensive line when he loses the duel, and from then on, Stones remains free throughout the play.

Briefly, when off the ball, Stones operated as the right-back in Manchester City’s defensive line, both in high-pressure situations (4-2-4) and during medium/low block scenarios (4-4-2).

Regardless of whether it’s Walker or Aké as the fourth center-back, it’s incredibly noteworthy that Manchester City became winners of the Champions League by playing in this manner throughout the entire knockout stage. The final becomes an even more significant milestone because Stones was, for many, the best player on the field (even though he was tactically favored for it, his composure with the ball was impressive). The materialization of this fact makes the rise of four center-backs as a trend in positional play undeniable. Therefore, it’s important to seek to understand what this represents for football itself.

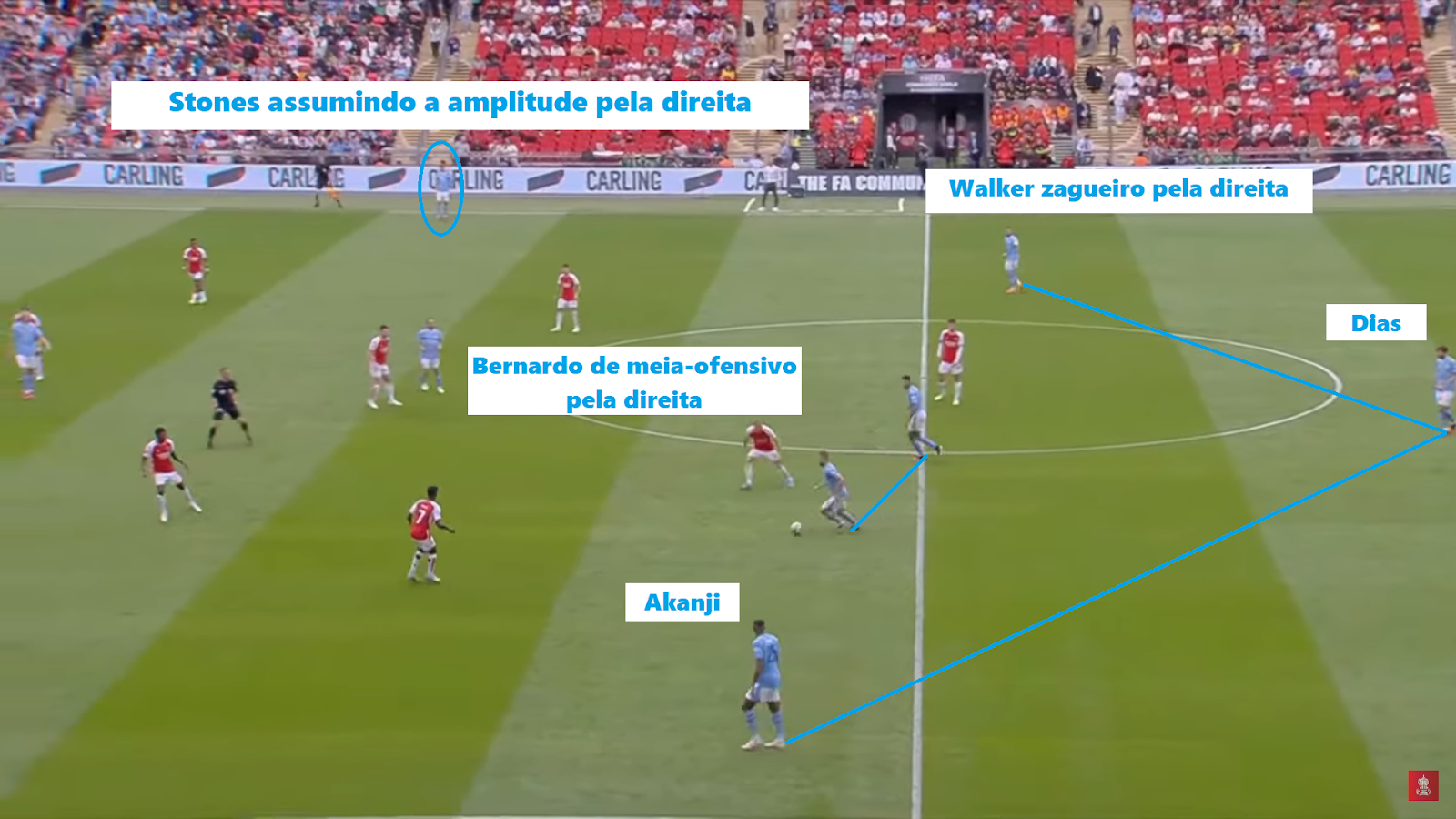

3 – Symbolic: Community Shield with 8 center-backs on the field

Moving on to the current season, the first clash between Arsenal and City, the main proponents of positional play at the moment, was almost as symbolic as the Champions League final. Eight center-backs at Wembley competing for the Community Shield. On the London side, Timber, Gabriel, Saliba, and White. On the Manchester side, Akanji, Dias, Stones, and, once again, I consider him a center-back, Walker. On this occasion, at least the two teams had distinct structures and functions, contrasting interestingly within the same positional principles.

3.1 – Arsenal

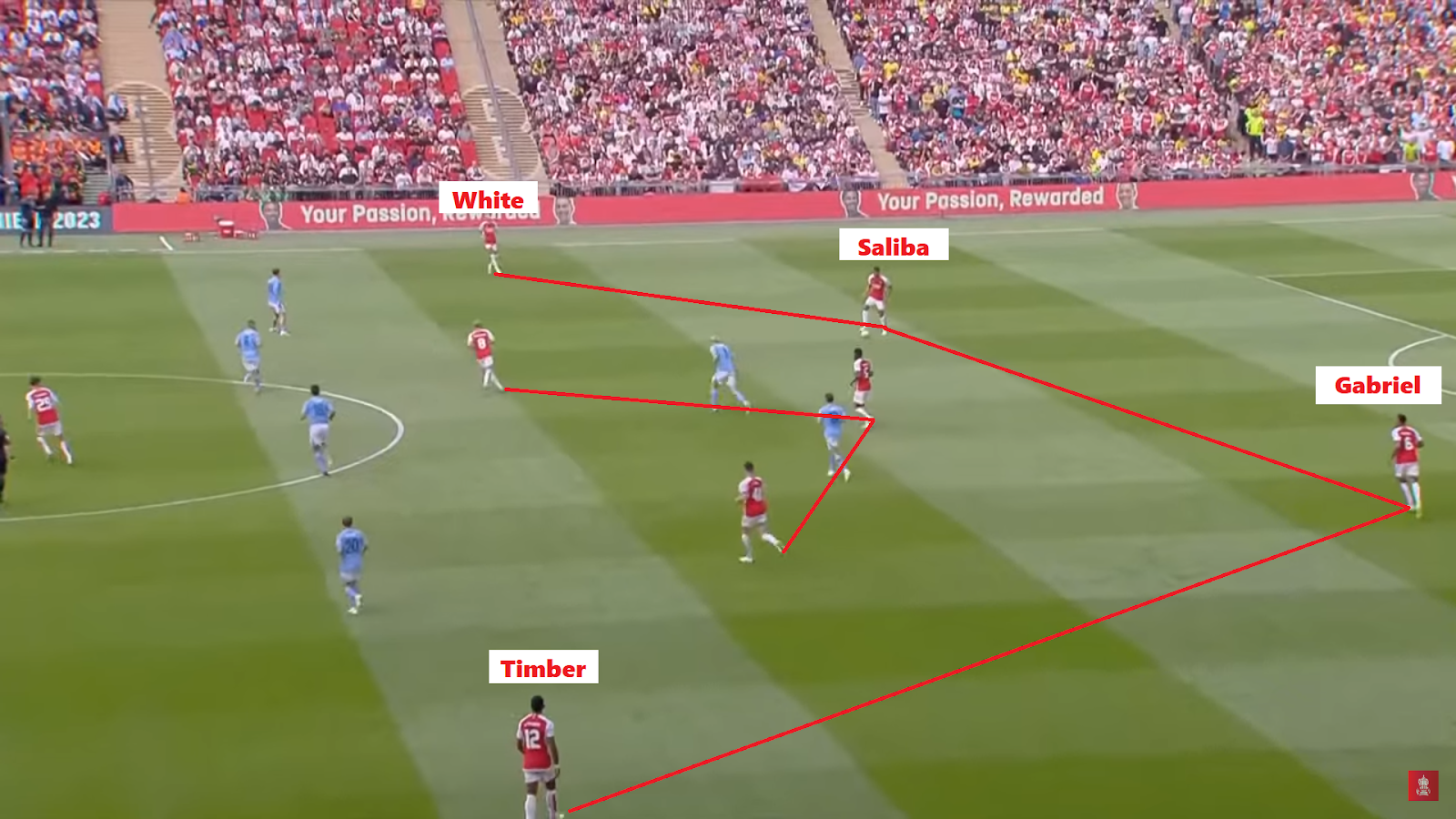

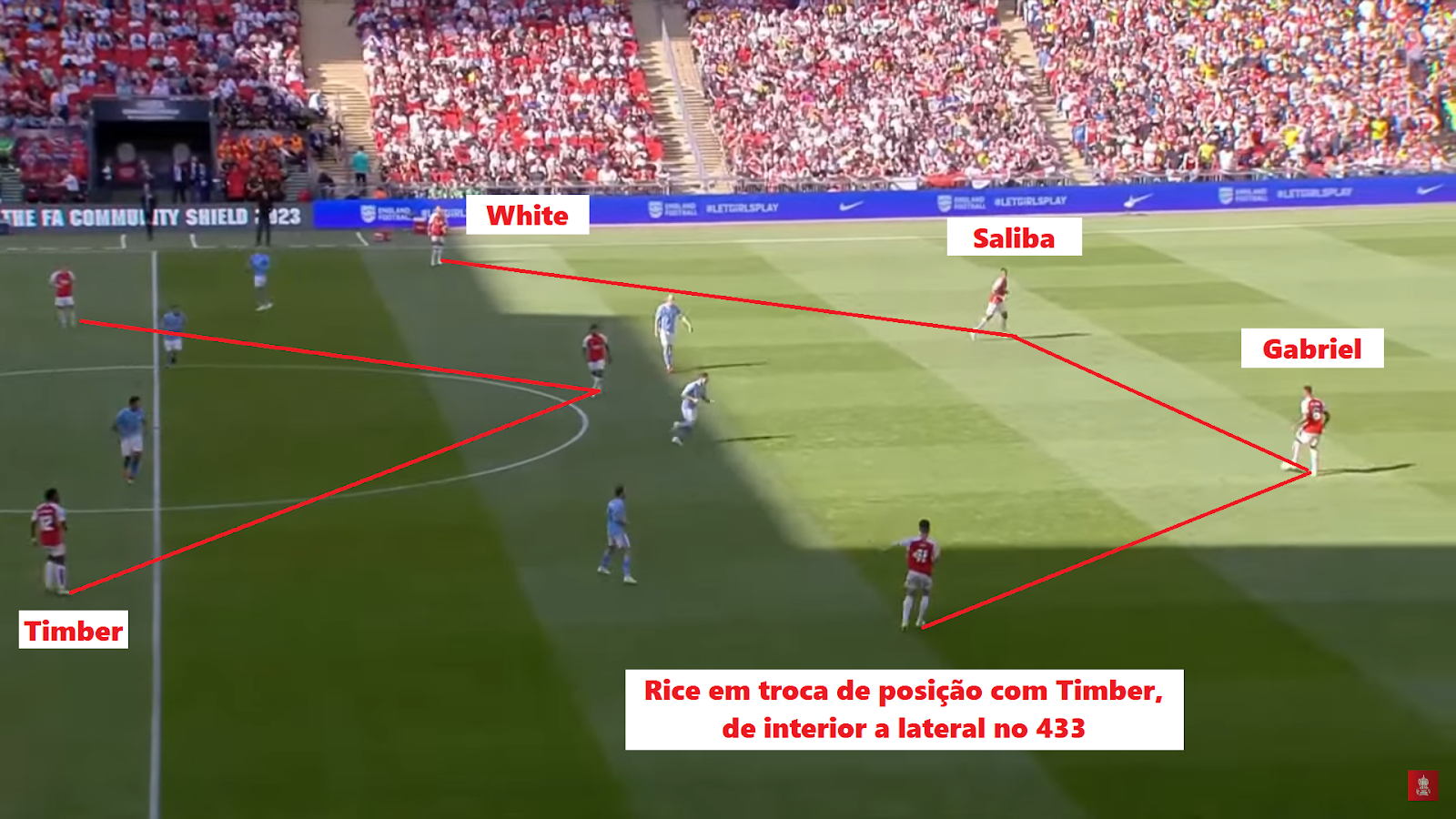

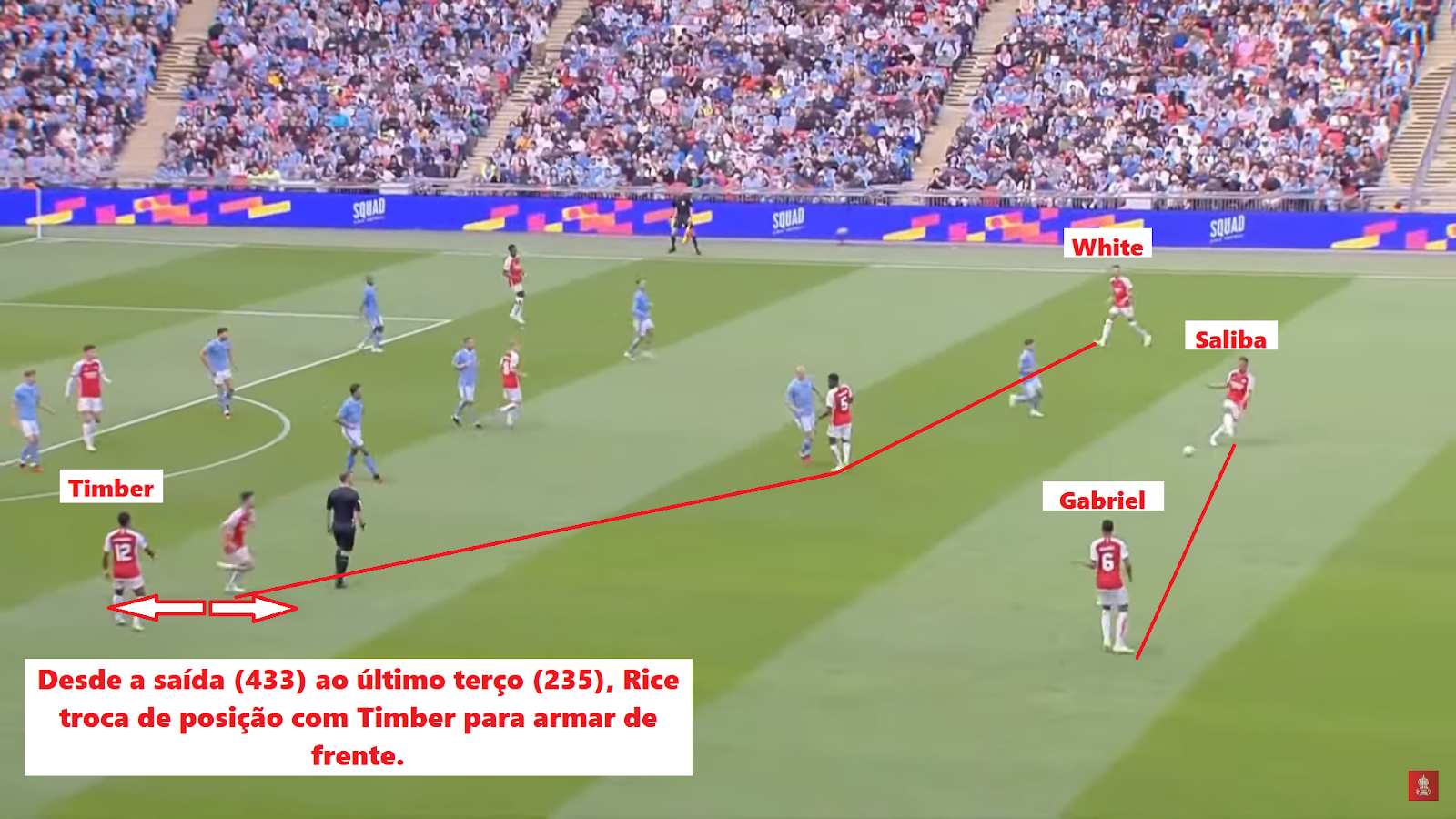

The Gunners took to the field in their traditional 4-3-3 base, with Ben White at right-back and Jurrien Timber at left-back. In midfield, the newly signed Declan Rice heavily influenced the dynamics of offensive organization, directly impacting the roles of the center-backs. The former Hammer is primarily a number 6, and to address the initial discomfort of playing as a left interior, he often dropped deep to help build the game from the back. To do this, he swapped positions with Timber, effectively becoming a left-back/center-back, slightly benting the team’s shape in the buildup. As a consequence, the Dutchman moved into a midfield role alongside Odegaard, and the team sought to capitalize on his speed and physicality by finding him in motion and exploiting overlapping runs with Martinelli.

When they beat City’s press and built possession in City’s half, the 4-3-3 transformed into a 2-3-5, with the same full-backs moving inside to shorten the distances to Partey. They maintained the dynamic between Rice and Timber and added the well-known rotation of triangles on the wings. In the second image, Ben White is in the position that would be Odegaard’s, and vice versa, linking up with Saka and the Norwegian midfielder.

3.2 – Manchester City

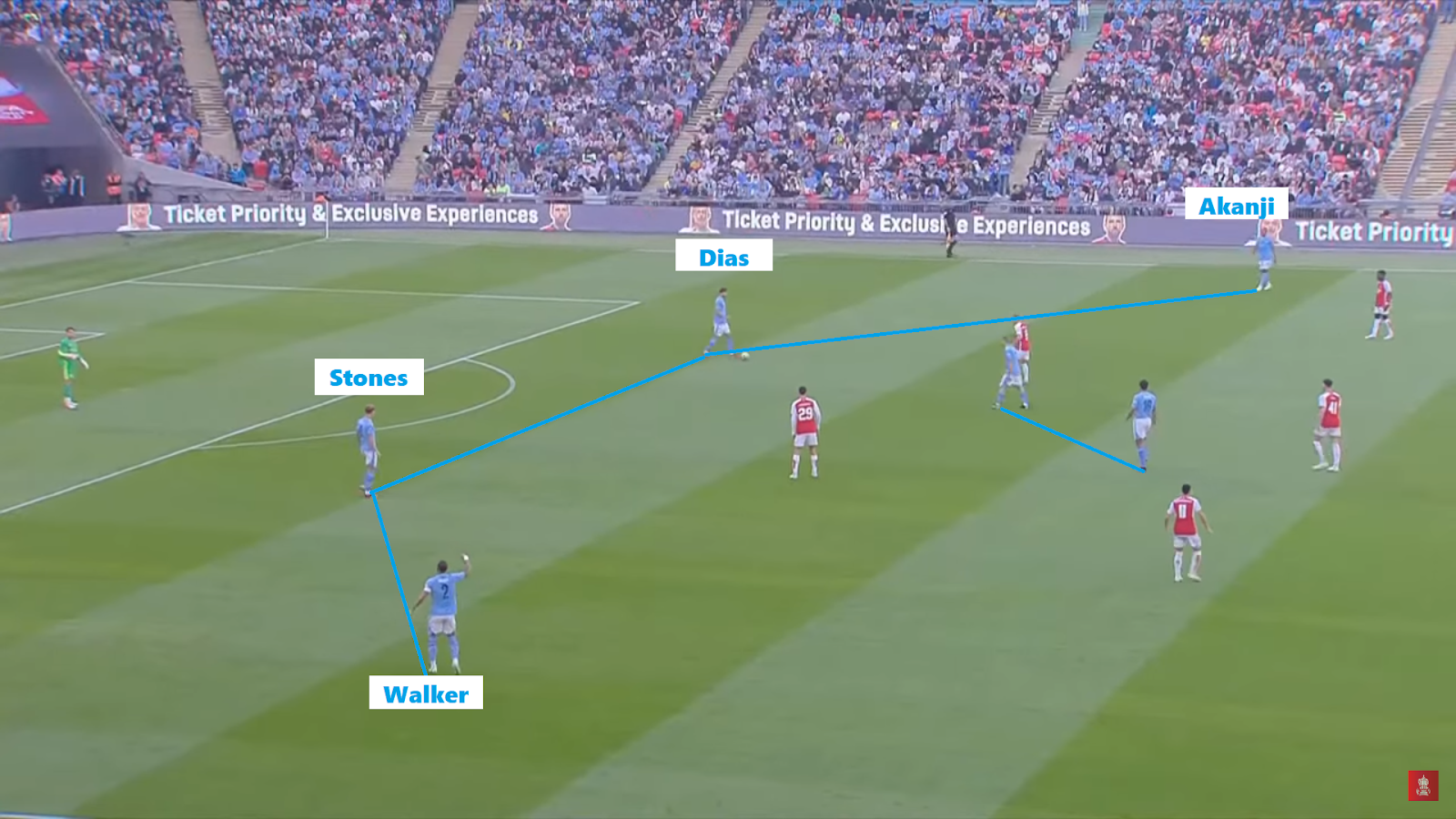

On the other side, Guardiola’s team lined up in the rare but already familiar 4-2-4 formation, with Haaland and Alvarez forming a striking duo, with the Argentine often taking up the high position in what we can interpret as a 4-2-1-3 when he provided support and occupied the zone between the lines. At the back were the four center-backs.

Like any formation with genuine full-backs, there is a structural difference between the buildup and the occupation of the attacking field. In the case of City, and especially Walker, they would push forward and take on the role of width. The following gif is an excellent example of Guardiola’s structural rigidity at the same time he allowed the center-backs to join the attack. While maintaining the 4-2-4 shape, Rodri dropped deep as a center-back as Walker pushed up to the wing, and Stones became the right-back. In response, Bernardo aligned himself with Haaland, and Julián dropped deeper as a midfielder. As the possession progressed, the ball shifted to the left, Rúben Dias advanced to exploit the space between the Arsenal center-back and full-back, and as a result, Kovacic dropped back as a left-sided center-back. It was imperative for Pep to maintain the foundation of the formation.

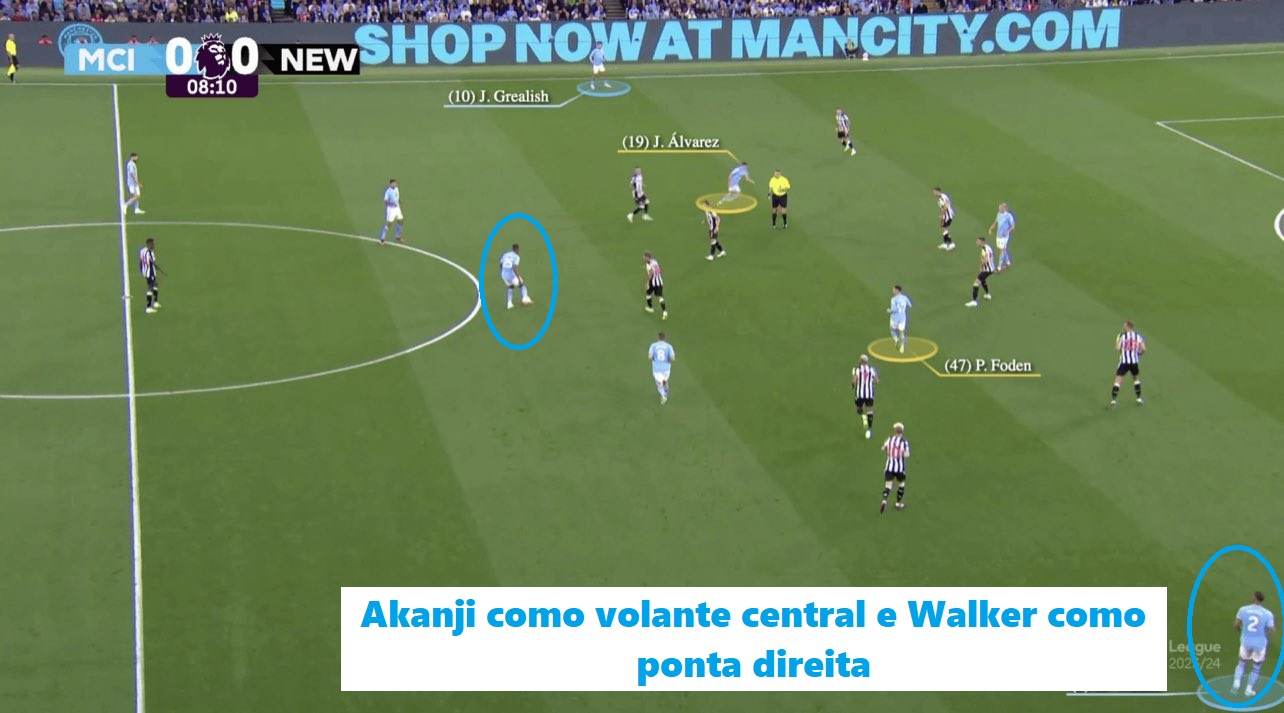

In the second half, Manchester City switched to a 3-2-5 formation, with Julián and Bernardo as attacking midfielders and Walker on the right-wing. However, in positional play, it doesn’t necessarily matter who occupies the space as long as it is effectively filled. Therefore, it was possible to see Stones and Akanji taking on the roles of the wide areas in this setup.

Passed, finally, the pitch-focused analysis, lets go to the conceptual discussion from behind

4 – The prerogative is purely defensive

“I would say that with 4 defenders, we defend our area properly… It’s our biggest step forward; now we like to defend, and even if we make mistakes, I have the feeling that we know how to defend.”

Pep Guardiola after the Champions League final

Guardiola’s decision is entirely based on defending better. The evolution of his system culminated in four center-backs, defensive specialists, to support it. It resulted in aiming for more efficient post-loss recovery, which comes naturally to the players since they are defenders, and the most secure defense of the penalty area, where they have spent their entire careers. There is no significant surprise factor in the presence of Akanji and Stones in midfield or out wide. What matters are their defensive qualities and how they can protect the team from situations that deviate from offensive organization.

Currently, the most crucial detail in City’s playing model is for their players to win defensive duels and ensure that possession is controlled for most of the time. Guardiola’s offensive organization system must be in operation at all times, turning its gears and bringing the team closer to the desired result.

5 – Risk reduction: Center-backs take fewer risks

“When people say, ‘Pep wants to control the ball for 90 minutes,’ yes, that’s what I’m working on every day, to have control of the game for 90 minutes.”

Guardiola in an interview with Thierry Henry

Having control means reducing risk and unpredictability. Given that Manchester City’s center-backs are all technically skilled and won’t make a mess when controlling the ball, having them on the ball is not risky; it’s quite the opposite. They remain center-backs. They won’t attempt unlikely dribbles or precise passes. Center-backs stick to the basics; they don’t get fancy. They’ve heard this their entire lives, and they won’t forget it overnight, especially since they won’t be encouraged to do otherwise. If there’s anything beyond the defensive characteristics of Akanji and Stones that interests Guardiola, it’s their lack of daring. The Catalan doesn’t want a surprising libero; he wants a center-back as we know them, as long as they are technically proficient enough not to hoof the ball, mishandle it, or cast doubt on possession when they have the ball at their feet. The goal is to ensure that the ball returns quickly after a loss and is unlikely to be contested after recovery.

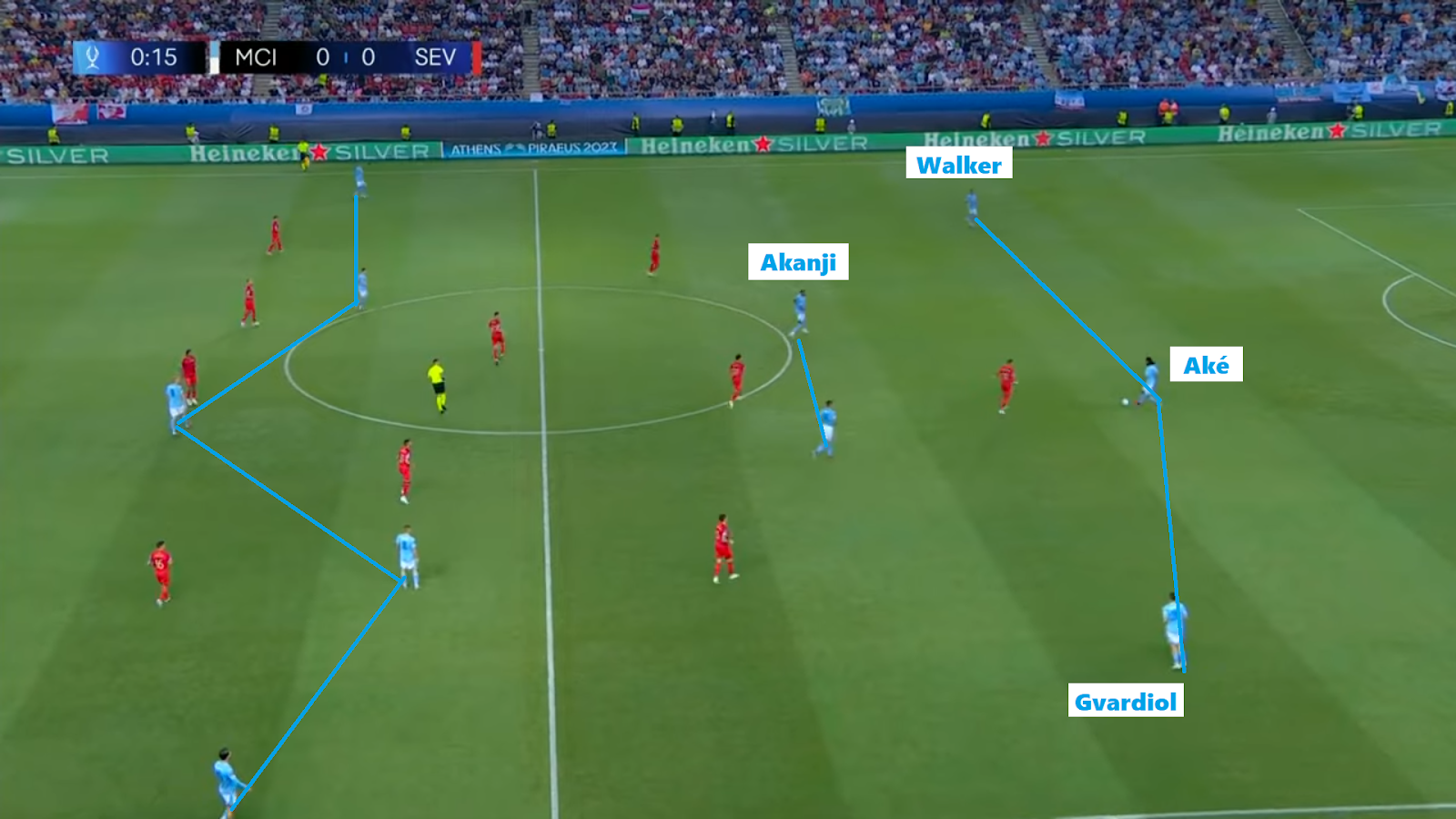

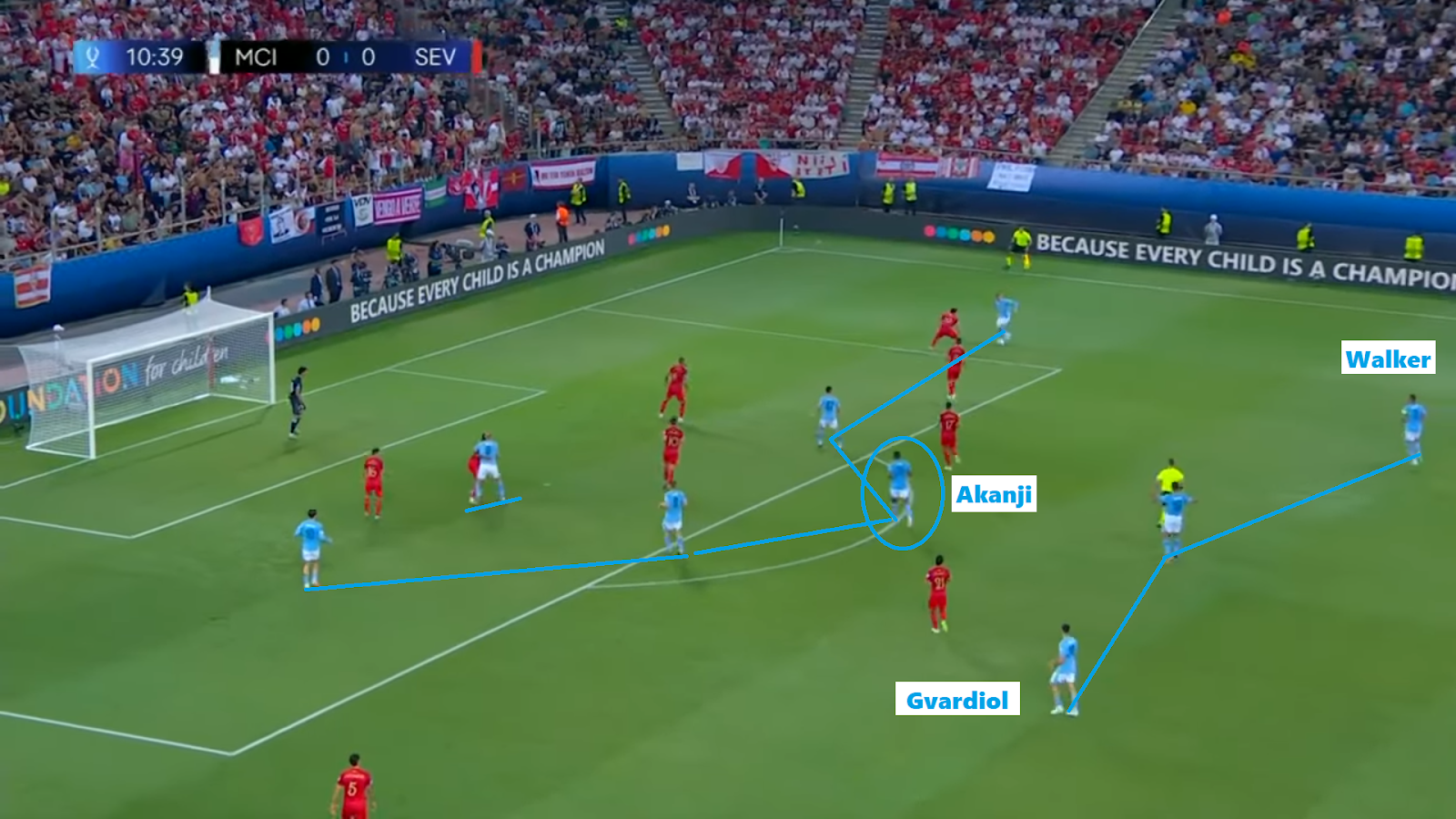

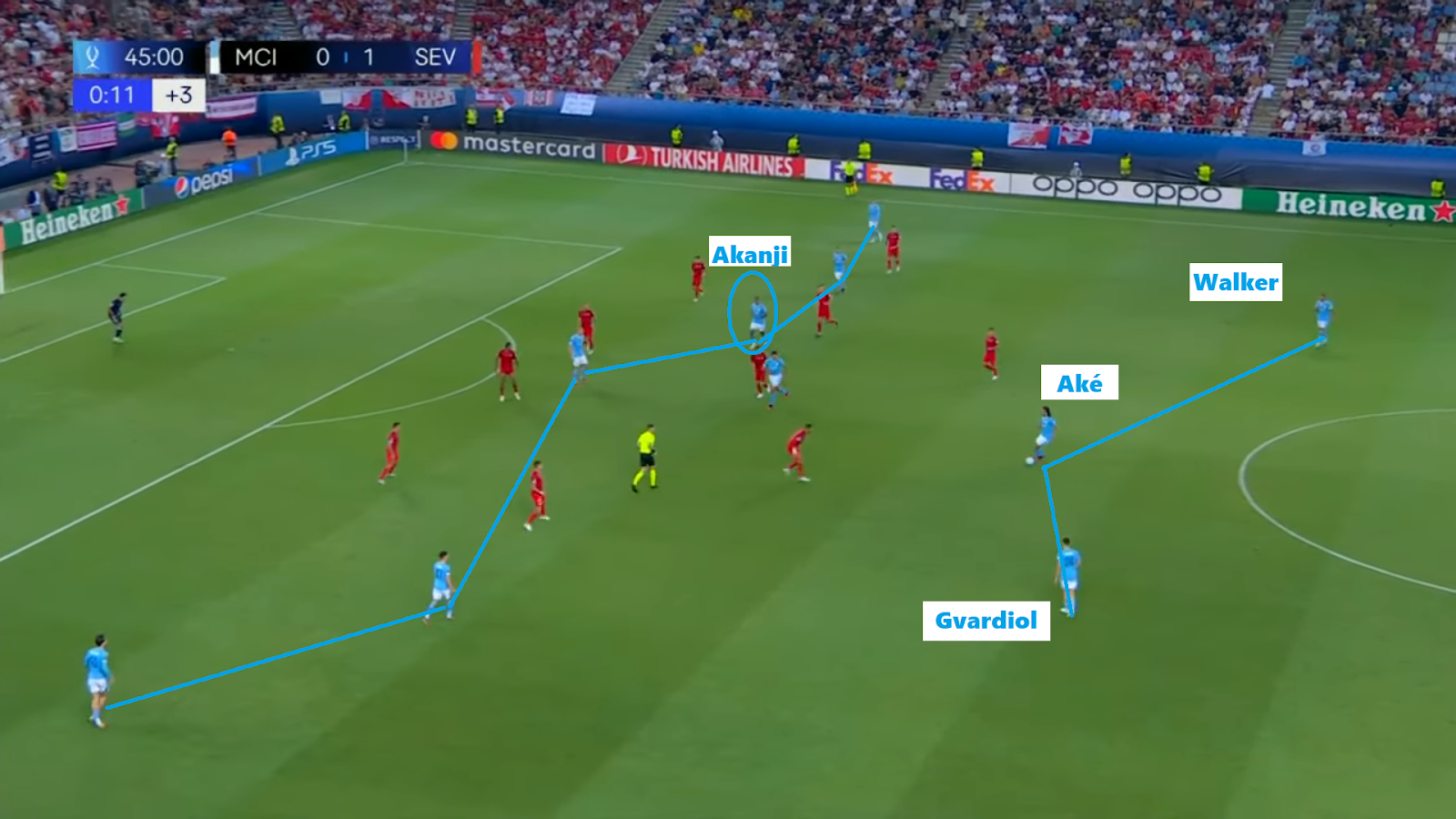

In the UEFA Super Cup against Sevilla, City returned to the 3-2-5 formation with a center-back as a defensive midfielder. This time, Akanji partnered with Rodri, and the newly signed Gvardiol was the left-sided center-back, alongside Aké and Walker – I take this opportunity to reaffirm my thesis that Walker is a center-back: even with Bernardo capable of playing as a midfielder, as he often did in the 21/22 season, and Palmer between the lines (or Julian, who was on the bench), playing the number 2 as a right wingback, Pep chose to have him in the center-back line.

As much of the game turned into a true attack against defense, City’s structure constantly became a 3-1-6/1-3-6. The logical choice might have been to push Walker forward, as he is accustomed to playing on the wing, and place Palmer in the middle. However, Guardiola, thinking defensively, kept the core intact and placed Akanji between the lines. That’s right. How does this benefit the team offensively? In terms of creation and scoring, absolutely nothing. However, in terms of control, it’s everything Pep wants. The Swiss center-back received the ball with his back to the goal and played it back. He didn’t attempt anything, embraced his limitations, and in doing so, extended City’s possession. Center-backs take fewer risks.

6 – It’s not really an innovation, but rather the reconfiguration of an old element

Guardiola didn’t invent the attacking center-back. We’ve heard countless stories about Beckenbauer, the legendary German defender, celebrated for his ball-playing abilities, dribbling past countless opponents, and leading the team’s attacks. We’ve also had our ears filled with talk about the libero (often used strangely to refer to the goalkeeper), who was, in reality, the “spare” player in the catenaccio system but acquired, at least in Brazil, the meaning of a center-back who pushes forward. In short, it’s an age-old conversation that didn’t come out of nowhere. There has always been, albeit rare, the figure of a technically skilled center-back who contributes offensively to the team.

Don’t get me wrong; it’s clear that modern football demands more technical ability from center-backs. However, the reasons behind this shift lie elsewhere. It has little to do with being in more advanced areas of the field and playing a more significant role in offensive production. Instead, it’s about executing short build-up plays and dealing with the increasingly common high-press situations in the opponent’s half. The fact that Akanji is used as a defensive midfielder or midfielder is driven by other motives, as explained throughout the text. Therefore, the correlation between the increased technical skill of modern center-backs, beyond the argument that it enables Guardiola’s risk-averse plan, considering the number of players with these characteristics, is untrue.

To recap, my point is that a center-back as a fixed midfield piece in a positional play model doesn’t bring any offensive advantage. What truly set apart and made the participation of a center-back in the offensive system beneficial for teams with a technically gifted player in the past, like Beckenbauer’s Germany, was the element of surprise. The center-back wasn’t always there, but they would come into the picture. They would arrive. That’s what disrupts the marking. The unexpected prolonged carry creates jumps out of position and, consequently, new passing lanes. The “tabelas” with an unexpected element is what confuses the defense and scrambles their reference points. It’s the value of a “center-back in attack,” sporadic and surprising, that gives you advantages with the ball. The value of a “center-back” in attack, always there, a standard part of the system, gives you advantages without the ball.

7 – The message is clear and contradictory: The system has surpassed the individual in importance

In the end, what this trend signifies, in my view, is that it makes little difference whether it’s a center-back, whose inventiveness is unquestionably inferior to that of a midfielder, playing the role in the system. What matters is that the space is occupied, a specific movement is executed, and the structure operates. It’s as if the system has become a larger, self-sustaining organism that conquers the field through its own automatic actions, emancipated from the essential qualities of the player. It appears that football is seemingly escaping its (increasingly less) inseparable chaotic ontology, moving closer to the planned ideal.

However, it’s true, and here comes the “contradictory” aspect, that all of this relies precisely on the individuality of the defenders. Paradoxically, it sounds like a surrender of the system to the talent it can’t achieve through mechanisms alone. Guardiola, by fielding four center-backs, admits that he was unable to devise a model that could encompass defensive organization and transition with the same effectiveness as the offensive aspects and that there is nothing more impactful in concrete football than innate talent and aptitude. At the same time, the decline in creativity among players in the offensive system goes almost unnoticed (in the eyes of those who see but don’t truly perceive), as the mechanism has already dissociated itself from individual qualities. Yet, it’s precisely the increase in individual skill in the defensive system that is targeted because it has not been able to become self-sufficient. In other words, hyper-systematized football, while attempting to negate the importance of the one who executes, the true protagonist, ends up falling into the dependence on them.

“Being a good defender, I consider the biggest talent in football. Now we have players who enjoy defending.”

Pep Guardiola