September 19, 2023 began with news that, although they had already been virtually announced in the previous days, didn’t fail to shake German football: Julian Nagelsmann accepted the proposal from the German Football Federation (Deutscher Fußball-Bund, or DFB) and will be the coach of the German National Team until (at least) the Euro 2024, which will be played in Germany. For the second time in his career, Nagelsmann will be assigned the difficult task of replacing Hans-Dieter Flick, but in a much more troubled scenario and in a much more arid tactical legacy than the one he received when he replaced Flick at Bayern Munich in 2021.

A change of command in a National Team so close to a relevant tournament (we are less than a year away from Euro 2024) always raises doubts: does the DFB really think that Nagelsmann is capable of solving the problems that Flick’s team had? Why the short contract, only until Euro 2024? Wouldn’t Nagelsmann be the long-term option among the others speculated (Van Gaal, Glasner, etc.)? Did the “ghost” of Jürgen Klopp and of the possibility, albeit slim, of signing him after the Euros influence the decision? But, for me, the most relevant question is different and says more about the coach himself than about the scenario in which he was inserted: which Nagelsmann will be the coach of the German National Team?

When Nagelsmann emerged into the world of football as a promising coach at Hoffenheim, he was always highly identified, celebrated and even criticized for his incredible tactical flexibility. “We change our system too much during games. We are not ready for this. We are not robots, we are humans. I love Julian (Nagelsmann), but sometimes we need three minutes after changing the system, because not every player understands or aren’t able to hear him because of the 50,000 fans,” said Croatian Andrej Kramarić about a discussion he had with Nagelsmann after a 2-2 draw with Borussia Mönchengladbach. Kramarić has always said that Nagelsmann is one of the best coaches in the world and their relationship has always been very good, but one of the coach’s problems was already apparent at the beginning of his career and was already bothering the players: Nagelsmann is restless, he wants to change details all the time, he feels uncomfortable when he’s not in control of everything, feels forced to make too many tactical tweaks and ends up confusing his players.

In parallel to this, Nagelsmann in his Hoffenheim days showed a strong inclination towards a more positional game, more specifically the Juego de Posición itself. It wouldn’t come as a surprise; he took over Hoffenheim at the beginning of 2016, at the height of Guardiola’s influence, who was still coaching Bayern Munich, on the football played in Germany. As if this wasn’t enough, his career as a coach began when, still in his early 20s, he worked under the command of Thomas Tuchel in the Augsburg youth teams. A few years later, Pep Guardiola himself would praise the way Tuchel applied the Juego de Posición to his Borussia Dortmund and would even state that, if the Juego de Posición were to succeed in Germany, this would inevitably involve Tuchel taking a leading role in the process.

But the positional influence would always go hand in hand with tactical flexibility in the young coach’s life. In the book Pep Guardiola: the Evolution, the author Martí Perarnau pointed out that Nagelsmann’s Hoffenheim had put into practice several principles of the Guardiolist Juego de Posición, although he didn’t practice it in a complete form, already indicating Nagelsmann’s willingness to negotiate principles and implement them in his team different ideas so as to make it richer.

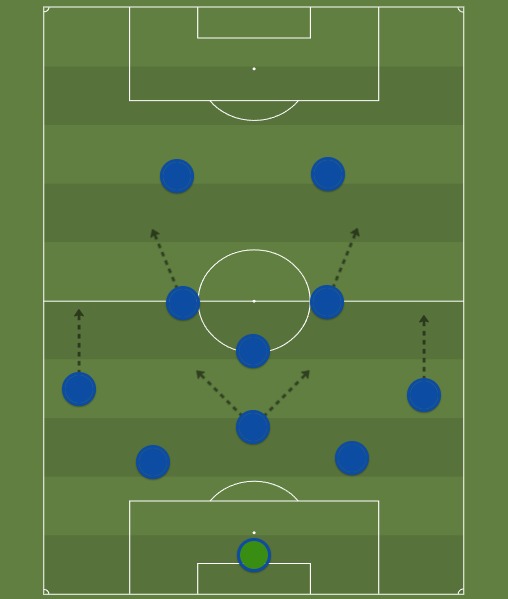

Despite frequent and restless changes, the solid tactical foundations of Nagelsmann’s football philosophy were already clear and defined. His Hoffenheim, like any good German team of the 21st century, was an absolute pressing machine; however, it did it in a very different way compared to another notable Hoffenheim coach of the decade, Ralf Rangnick. While Rangnick, in the best gegenpressing style, sought to retrieve the ball as quickly as possible to find the opponent disorganized and destroy them with quick and relentless counterattacks, Nagelsmann preferred to use pressure to regain possession and control of the game, happily maintaining possession and building up the play more slowly and calmly. With the ball, Hoffenheim started in a 3-5-2 (or 5-3-2) shape and preferred to spread out its players on the pitch to form more complex passing lanes and move higher up the pitch in a more methodical and thought out way. The team had a very offensive DNA, and Nagelsmann used the versatility of the wingers and midfielders and the defensive security of the three centre-backs to place several players in the attacking third: his offensive structure often looked like a 3-1-6 when the wingers and midfielders joined the attackers. From this, Hoffenheim had a positional structure, but it proved to be more fluid when moving the ball and its players than a more classic and orthodox Juego de Posición.

In his next job, at RB Leipzig, Nagelsmann maintained his tactical flexibility, but learned from his problems at Hoffenheim and began to design more well-defined principles to avoid making his players confused. Some things remained the same, such as Nagelsmann’s affection with 3 centre-backs to have a more well-sustained and thought out early build-up and greater defensive security when placing players in the attacking third (although, unlike Hoffenheim, Nagelsmann’s RB Leipzig didn’t always started games with 3 traditional centre-backs and 2 traditional wing-backs and often defended in a line of 4 defenders; when attacking, however, one full-back moved higher-up as an attacker and one stayed back as a centre-back. Versatile names who could play both at centre-back and full-back like Klostermann and Halstenberg started to be very valuable to Nagelsmann). His tendency to organize the team in a 3-1-6 on the offensive structure also continued, but often starting from a 3-4-3 with the wing-backs advancing to join the attackers and one midfielder (Sabitzer, usually) playing more advanced than another (Laimer, normally, although Laimer has also played as a wing-back under Nagelsmann at Leipzig). Furthermore, the figure of the central defender acting as a sweeper, which already existed at Hoffenheim, was consolidated at Leipzig in the figure of Dayot Upamecano.

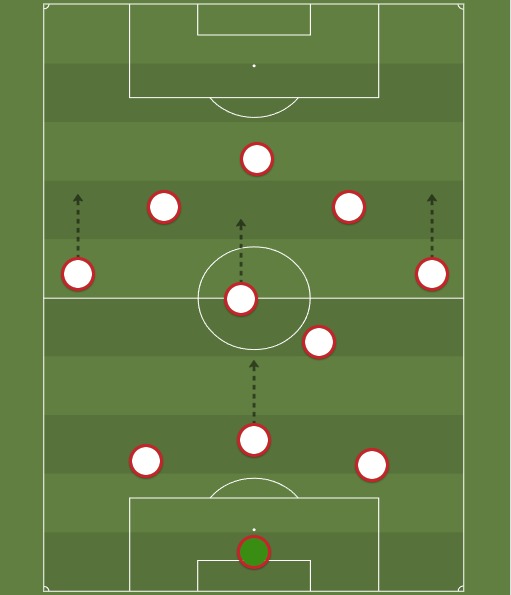

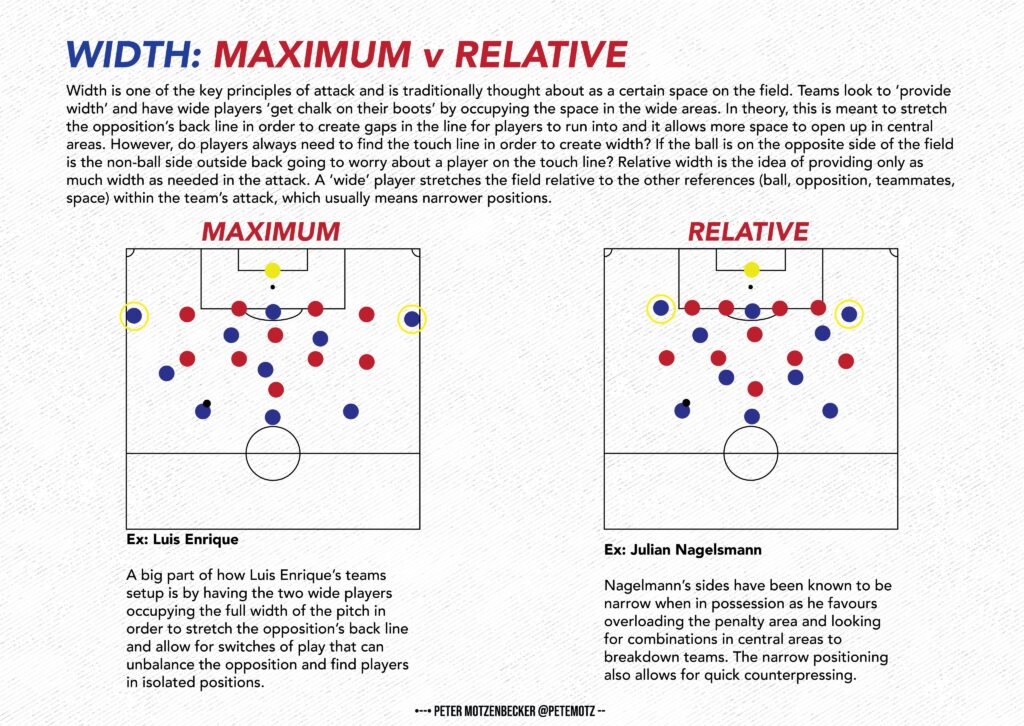

But the most relevant thing about Nagelsmann’s work at RB Leipzig (besides, of course, the sporting success, leading the team to a Champions League semi-final and to a German Cup final) was a clearer vision of what the tactical principles of Nagelsmann were. He continued to start from more positional ideas, spreading his players in different zones of the pitch to create passing lanes and move down the pitch from them, but these zones began to seem more like starting points than delimiters for the players’ movement, and RB Leipzig had a very fluid structure when they had the ball. Furthermore, Nageslmann gave up having two wingers (or wing-backs) stuck on the touchline to stretch the opponent’s defensive line as wide as possible and began to bring players closer together and narrow his team in the attacking third to attack the area with more players, shorten the passing lanes and facilitate the counterpressing. The wingers were still fixed on width, but they were at the limit of the opponent’s defensive line – the so-called relative width.

“Here we play closer together. We rely on each other so we can give the game more speed. If we play more spaced-out, we can’t play as fast as the coach wants us to. That’s why we want to play as close together as possible, almost like Five-a-side Footbal. The smaller the space, the better, because the ball moves faster. We attract more rivals that way, but we need to know how to play under pressure. If we succeed, we open bigger spaces and we’re able to attack with more depth” — said Dani Olmo in an interview to El País when asked if Nagelsmann’s Leipzig played the Juego de Posición. Dani Olmo’s speech summarizes Nagelsmann’s philosophy at the time very well: despite having more positional principles, Nagelsmann preferred to bring his players closer together and give them more freedom. Firstly, as said before, bringing your players closer together creates shorter passing lanes, makes the passes faster (since the ball has to travel a shorter distance to get from one player to another) and facilitates counterpressing, because the team has more players in the area where they lose the ball and, therefore, are able to pressure the opponent more effectively. However, the main advantage that Nagelsmann seeks to achieve with these approaches goes a little further and Dani Olmo’s answer explains this very well.

In a classic Juego de Posición, the coach seeks to occupy the spaces of the pitch by placing their players to the zones he deems most strategic. Then, the team moves the ball between these zones, taking the ball to the players and not the players to the ball; players must wait for the ball in the zones determined by the coach. When moving the ball across the pitch, the opponent is forced to run after it, which opens up spaces on the pitch – and, as the players are occupying the most strategic spaces, someone will eventually be free. This is one of the main principles of the Juego de Posición: occupy the spaces with your players and move the ball between these spaces until a player is free.

“What moves is the ball. Looks like we are moving the players, but what moves is the ball. The people believe, ‘oh, look how they move’. No. What moves is the ball. Everybody has to be in their positions. When you move much, that’s not good. The ball comes to where we are, we don’t go where it is to pick up the ball” — Pep Guardiola.

Wings of Desire – Nagelsmann’s most ambitious flight (so far)

The love story between Nagelsmann and Bayern Munich had been in the making for a long, long time: born and raised in Bavaria, Nagelsmann has stated on numerous occasions that he is a Bayern fan. Apparently the feeling was reciprocal; while Nagelsmann was still coaching Hoffenheim’s youth teams, Bayern tried to sign him for their own youth team. Still under contract with Hoffenheim, Nagelsmann politely declined the offer and preferred to give it time. Well, he wouldn’t have to wait long, and RB Leipzig’s relevant campaigns in the Champions League in 2019/2020 (semi-finalist) and in the German Cup in 2020/2021 (runner-up) stamped his passport to return to Bavaria and to finally achieve his dream of coaching Bayern Munich. The task would not be easy, as Nagelsmann would arrive to replace Hans-Dieter “Hansi” Flick, who had just won a sextuple (all 6 possible titles in one season) in charge of Bayern, but (apparently) the club’s confidence in Nagelsmann’s work was not lacking. After all, the Bavarian board spent around 25 million euros to sign him from RB Leipzig and offered him an long 5-year contract, with an annual salary of 7 million euros.

Nagelsmann’s first season at Bayern was somewhat strange. The team won the Bundesliga with an 18-point advantage over Borussia Dortmund, second place finishers, and scored incredible 97 goals in the league, Bayern’s fourth highest score in the history of the Bundesliga, only behind the 1971/1972 team, which had with Müller and Beckenbauer and scored 101 goals, and both the Hansi Flick’s teams (100 goals in 2019/2020 and 99 goals in 2020/2021). In parallel to Bayern’s (expected, let’s be honest) dominance in the national league, the team was eliminated from the German Cup in a 5-0 trashing suffered to Borussia Mönchengladbach (which would become a thorn in Nagelsmann’s side in his spell at Bayern) and fell in the Champions League to Villarreal in the quarter-finals of the tournament, still considered the biggest surprise of that edition of the tournament.

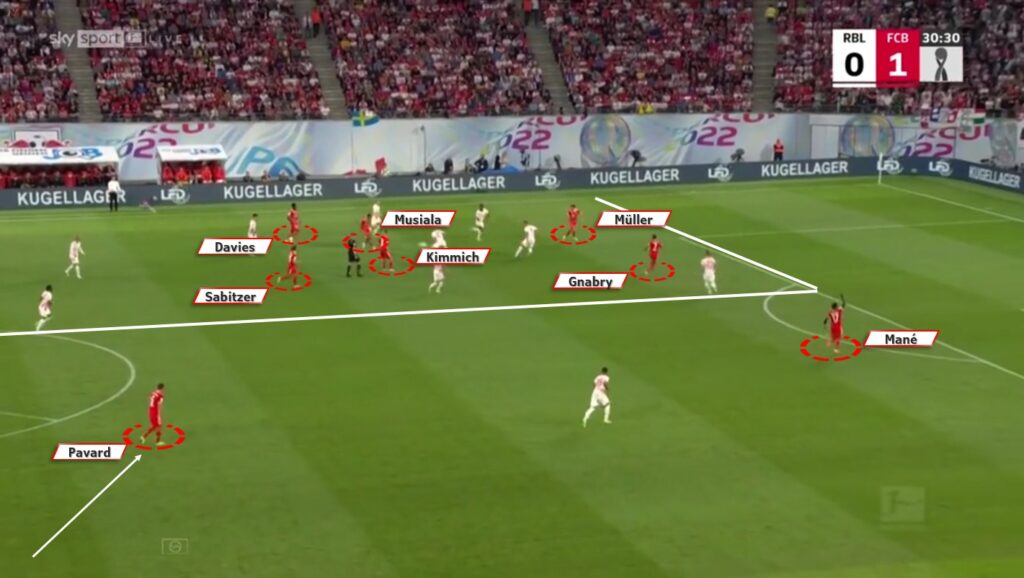

Leaving the most superfluous analysis of the results and moving on to an analysis of what happened on the pitch, Bayern showed several principles already known to Nagelsmann: a tendency to structure themselves with 3 defenders while attacking, offensive organization in a 3-1-6 and a game clearly slower and based on possession than Flick’s Bayern, which relied much more on aggressive pressing and fulminating counterattacks.

But going beyond these three main principles, something was indeed strange. Perhaps influenced by the tactical heritage of Flick’s team, which sought to accelerate and verticalize plays at all times and focused much more on quick external play with the wingers than on a slower internal play, Nagelsmann was more positional than ever. Even at Hoffenheim, when he was at his closest to the classic Juego de Posición, Nagelsmann wasn’t so rigid and his team played a more fluid structure, which sought a slower and well-worked game from central lanes. His Bayern, in turn, was a team with several “positional addictions”. Instead of trying to spread his players across the pitch in the most strategic way that would generate better passing lanes and possibilities for interaction as in Hoffenheim, Bayern’s Nagelsmann clearly mechanized principles in order to transform them into mechanisms and fixed these mechanisms to gain speed and objectivity in the circulation of the ball, even if this reduced the possibilities of interactions between the players. Bayern in the 2021/2022 season was the most repetitive and mechanized team of Nagelsmann’s career, which used indiscriminately fixed mechanisms that were easy to reproduce. We begin to see here another side of the young coach who was already restless about changing tactical schemes during his time at Hoffenheim: Nagelsmann’s insistence on having control over everything. As the season progressed, his team became more rigid. The 3-1-6 stopped being a starting point for his players, as in the Leipzig days, and began to become a rigid structure. Nagelsmann began to specialize his players, simplifying the interactions between them to suit the structure’s template, directing each player’s actions and decisions towards a specific task. Kimmich was the main distributor of the game and was the one who decided where the attack would go; the wingers (now much more fixed on space than before) had to win physical and/or speed duels to gain superiority on the flanks and cross to the box (so much so that, when Davies was injured, Nagelsmann preferred to add another winger to the team – Coman – rather than change the left back profile); interior attackers should attack the box to take advantage of these crosses. More than ever, Bayern was divided into two blocks: the 4 defending playmakers (3 defenders + Kimmich) and the 6 finishing attackers. Nagelsmann even had a delicate discussion with Lewandowski when he wanted to change the way the Polish striker headed the balll; this summed up the players’ discomfort in having to fit into the tactical structure. “As a coach, I am where I am today because I had success through a certain training philosophy — complex exercises, tactical behavior to adapt to the opponent. Bayern players weren’t used to this,” said Nagelsmann at the end of that season.

Nagelsmann could have insisted on the same idea (after all, despite being unpopular, it was what guided Bayern to a Bundesliga title with the fourth best attacking record in club history), but he preferred to take a step back and listen to his players. “In my second season, I will somewhat deviate a bit from my path. […] I’ve learned over the past season how important each individual character is to form a team. That’s partly even more important than teaching tactics. […] I learned how to communicate with the leading players and let them take part in my ideas. […] I’ve been on the phone with several players during vacation. I told them about what I want to adapt: more focus on ourselves and less on the opponent. I also asked for feedback from them. […] Maybe I underestimated that face to face conversations are more important for some players than I would have imagined as a coach. The players have to feel that they’re being noticed by the coach”, said Nageslmann at the beginning of the 2022/2023 season.

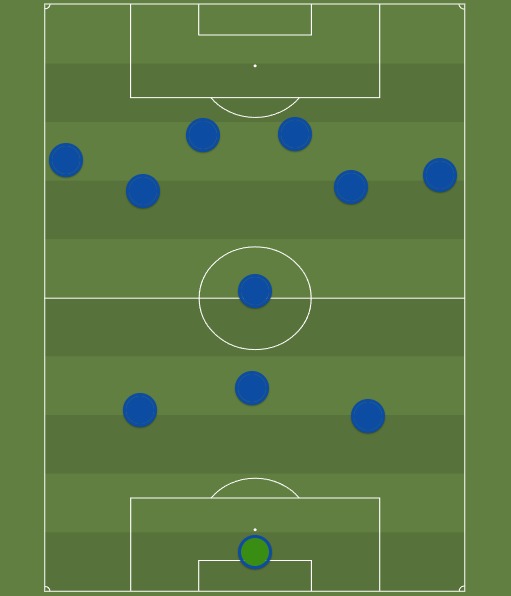

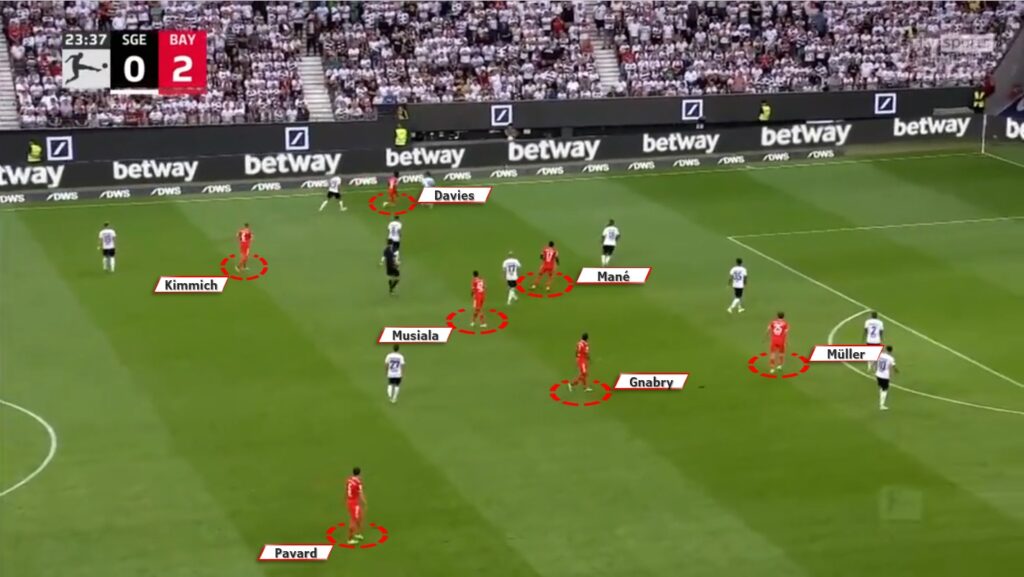

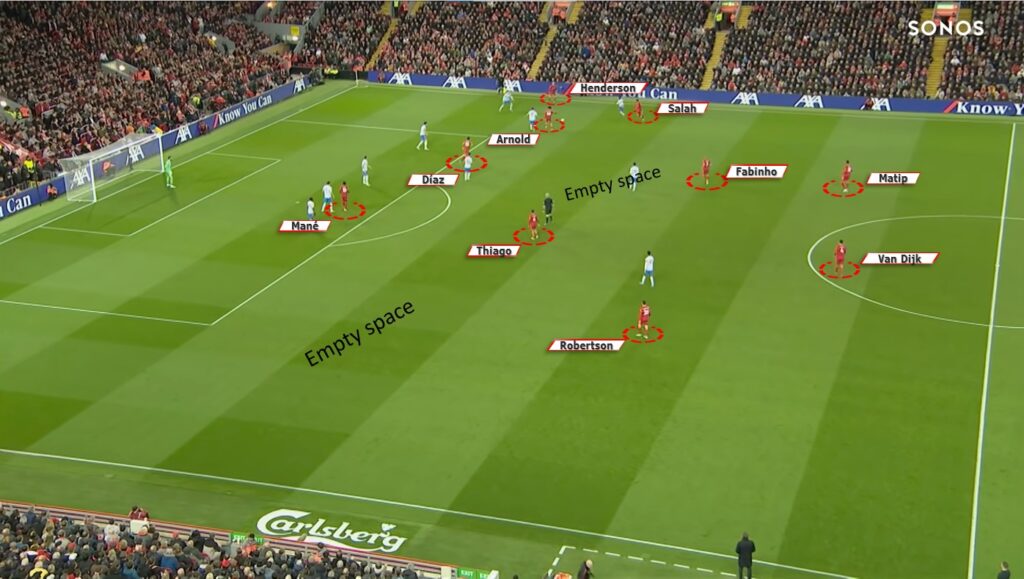

These words were not empty, and Nagelsmann did indeed radically change the way Bayern played. First, the coach sought to understand how each player felt most comfortable on the pitch to create a tactical structure that would suit that, not choose a tactical structure and try to fit the players into it. Thus, Nageslmann started to follow a philosophy much more similar to Ancelotti’s than Guardiola’s. “The solution isn’t in adaptation, but in change; or rather, in choosing a system that adapted to my players, and not the other way around”, says the Italian. “The coach sees the whole, combines individual qualities and makes up the team”. Still following Ancelotti’s idea, who says that “spaces are created by moving”, Nagelsmann, based on the principle of fitting his players in the pitch on the way each one feels more comfortable, set up a system that was based on natural movements (or natural roles) of each player to move down the pitch. Instead of taking the ball to the players, like at Hoffenheim and in his first season at Bayern, Nagelsmann took the players to the ball and set up a structure that drove the ball to the attack and made the team gain meters on the pitch from each player’s individual movements. This, combined with Lewandowski’s departure which, despite being greatly felt due to the lack of goals that this would cause to the team, ended up freeing Bayern from an addiction of always looking for crosses for the number 9, ending up resulting in a very mobile team, completely free of positional constraints and the need to respond to a macrostructure, which moved down the pitch based on the movements of its players. It was the Bayern of the role-driven, relationist attack.

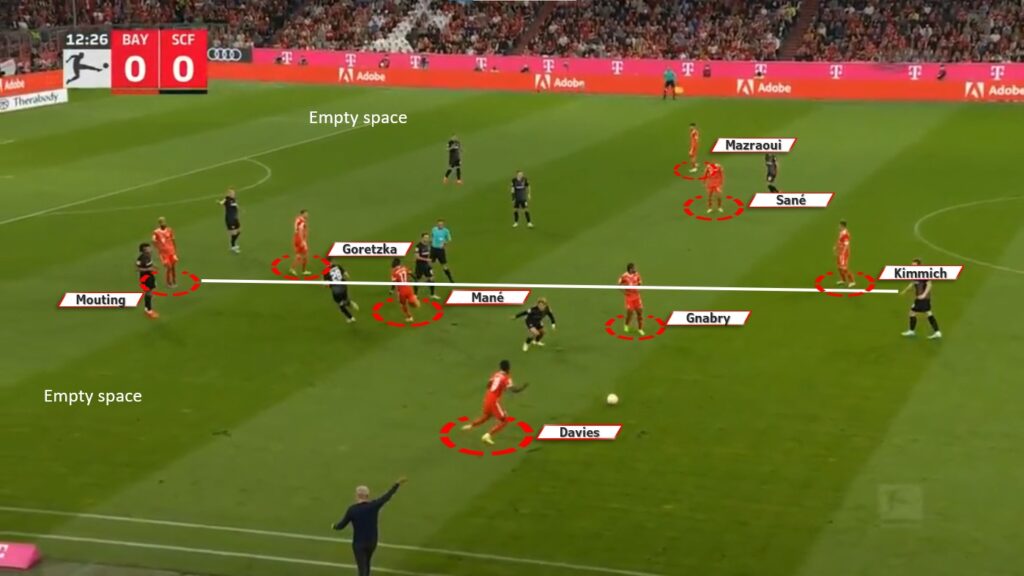

Bayern at the start of the 2022/2023 season was extremely relationist and role-driven. Nagelsmann had abandoned all his positional principles and invested his team’s entire possession structure in the movements and roles of his players, not the positions. It was a completely asymmetrical team, which gathered all the players around the ball and rarely positioned anyone on the opposite side to receive an inversion. The team’s movement logic was deeply based on pass and move, that is, players passed the ball and immediately overlapped to occupy an empty space. It was the more radical version of the most interesting principles of Nagelsmann’s Leipzig: that Bayern gathered players around the ball and sought to generate empty spaces on the pitch through the players’ movements so that they could infiltrate these empty spaces, giving a lot of depth and dynamism to the attack. The Bavarians ended the first half of the season as the leaders of the Bundesliga and in first place of their Champions League group with 18 points conquered out of a possible 18: 100% record in a very complicated group with Barcelona and Inter Milan, and only conceding goals in one game (in the 4-2 victory over Viktoria Plzen).

Bayern ends the first half of the season to stop their activities because of the World Cup in the best possible way, but returns from the World Cup break to face the second (and more important) half of the season in the worst possible way. In addition to the players returning physically very worn out by the absurd sequence of games that playing a World Cup in the middle of the season causes, which would make it harder for them to perform the long and constant movements that the relationist principles would need them to do, Nagelsmann saw a very demoralized squad mainly because the German players (Neuer, Kimmich, Sané, Musiala, Müller, Goretzka), the core of the squad and both technical and moral leaders, had just suffered the blow of elimination in the group stage for the second consecutive World Cup. Therefore, given the delicate physical and mental state of his players, Nagelsmann was afraid to return to the role-driven attack that had been so successful because he didn’t have much confidence that his players would be able to perform with such freedom and responsibility on the pitch and ended up returning to the traditional. Thus, for the second half of the season, Nagelsman returned to a rigid, extremely positional 3-1-6, with fixed and easily reproducible mechanisms so that his players were not so demanded and had a fixed and simpler game plan in their minds.

Thus, Nagelsmann qualified Bayern for the round of 16 of the German Cup and for the quarter-finals of the Champions League, beating Messi and Mbappé’s PSG. However, the drop in the quality of the team’s football was visible: the game was much more mechanized, bureaucratic, based much more on the volume than on the quality of chances to win the match and clearly had much fewer offensive weapons to hurt the opponent. This drop in performance was greatly reflected in the Bundesliga. Bayern started January with 3 draws in the league, then won 2 times, then were defeated by Borussia Mönchengladbach, then won 3 more times and then lost to Xabi Alonso’s Bayer Leverkusen. Between the return of the World Cup and the first International Break of the year, Bayern played 10 Bundesliga games, winning 5, drawing 3, losing 2 and gaining 18 points out of a possible 30, that is, a 60% record. A somewhat melancholy mark when compared to the first part of the season, where Bayern played 15 games, drew 4, lost 1 and won 10, winning 34 of the 45 possible points for a 76% record on the league, which only becomes more melancholic when you notice that Bayern’s drop in performance allowed Borussia Dortmund to take the lead in the Bundesliga right before the International Break, with the next matchday of the league being precisely a game between Bayern and Dortmund. Thus, in March 2023, in a move that surprised everyone, Nagelsmann was fired from Bayern Munich and replaced by Thomas Tuchel, his former teacher and an already known dream to the Bavarian board. When asked about the change, Oliver Kahn, then CEO of Bayern, said that he felt that the team’s football declined after the return of the World Cup (just when Nagelsmann returned to his old positional vices) and saw that the treble was threatened (interestingly, replacing Nagelsmann with Tuchel, a much more convinced and irreducible positionist, Bayern was eliminated from the German Cup in the new coach’s second game in charge, was trashed by Manchester City in the Champions League quarter finals and won the Bundesliga only on goal difference and counting on a great help from Borussia Dortmund, who only needed to win their last round game at home to become league champions and ended up drawing). Thus ended Bayern’s story with Nagelsmann, something that seemed like it would last years and didn’t even complete two seasons.

However, I purposely left out one of the most relevant (and interesting) pages of Nagelsmann’s tactical transformation at Bayern. Between the ultra-relationist 4-2-2-2 at the beginning of the season and the ultra-positionist 3-1-6 at the end of the season, Nagelsmann found a third way for the team. In mid-October, just before the World Cup break, Bayern played in what we can call a “German 4-2-3-1”.

A bit of context before we continue, German football, due to its geographical and cultural proximity to Hungary and especially Austria, ended up inheriting a Danubian football culture, more focused on role-driven attack and relationism, seeking to build advantages on the pitch through movements and roles of players rather than through their positions. However, due to its cultural particularities, German football ended up developing towards a more vertical profile, with more transitions, using the role-driven attack and the relationist principles more as a weapon to shorten the distances between players, accelerate the circulation of the ball (making it faster, more unpredictable and intense) and opening up empty spaces from the players’ movements rather than actually enhancing technique and individual talent, as in the Danubian and South American relationist tradition.

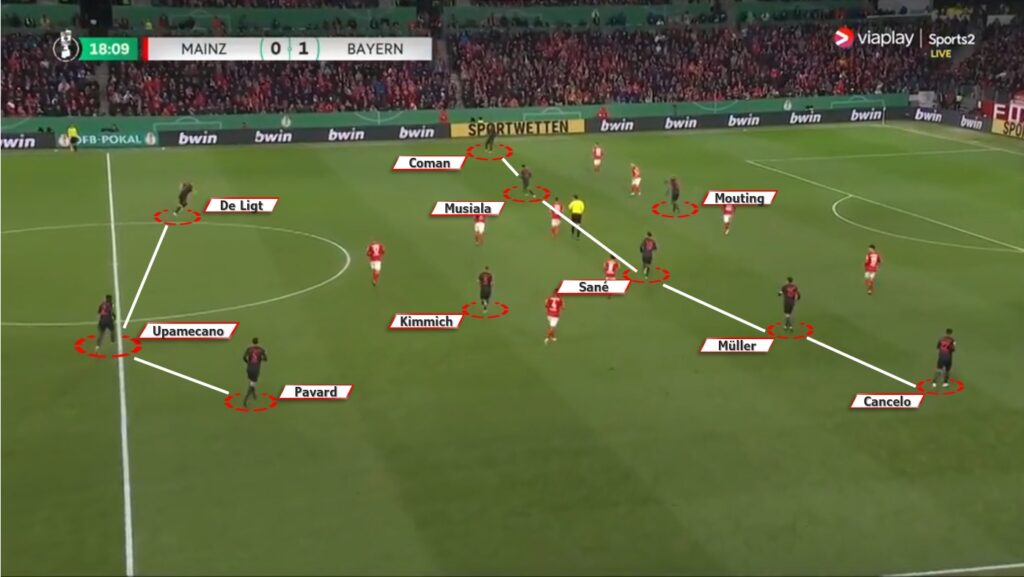

The more “nationalist” version of Nagelsmann sought to build a team in a mix of a 4-2-3-1 with a 4-3-3. Starting with a traditional line of 4 defenders, Nagelsmann uses 2 midfielders (Kimmich deeper and Goretzka higher) and a 10 (usually Sané) who could be closer to the midfielders (4-3-3) or to wingers Gnabry and Mané (4-2-3-1). In the center of the attack, Bayern once again had a classic number 9 on Choupo-Mouting.

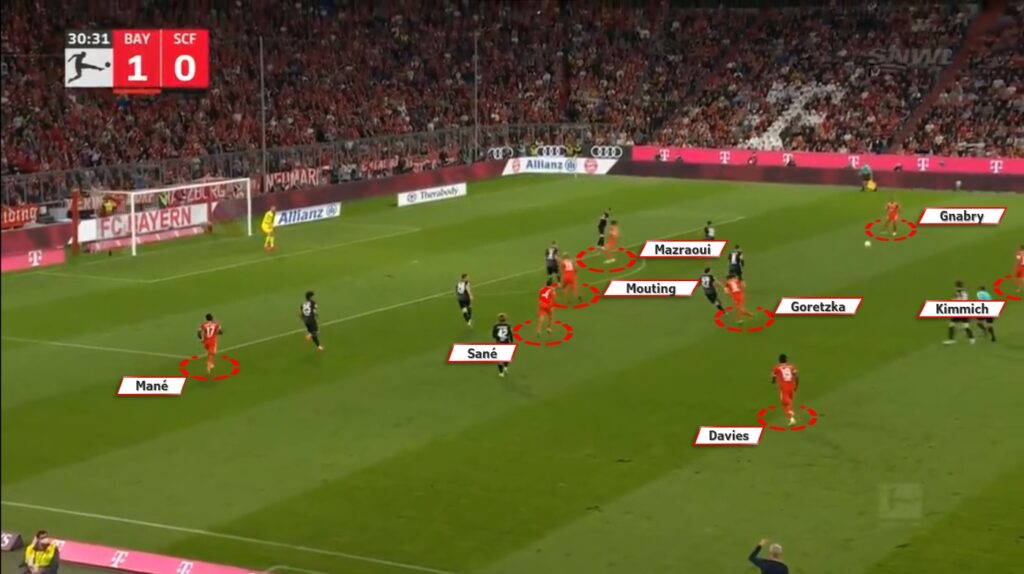

Bayern’s great performance with this new style was the 5-0 win over Freiburg on October 16, 2022. It was, without a doubt, a more positional team than the one that started the season: a team more spaced out across the pitch, with some principles (albeit weak; I’ll talk more about this later) of offensive zones and was much more willing to explore the wings than Bayern’s relationist 4-2-2-2, which concentrated all the play in central lanes. Mané was most affected by the change: he started the season as a central second striker and, at this new Bayern, he played as a very classic winger, more reminiscent of his first moments at Liverpool. Gnabry also stopped being a central attacker and played wider, but he drifted through central lanes way more than Mané. Sané, the number 10, played a little more to the right, and left a space on his left for Goretzka to infiltrate (in a very different idea, however. Instead of using Goretzka’s infiltration power to fix him in space, like in Bayern’s 3-1-6, Nagelsmann used this to enhance his infiltration in empty spaces, allowing longer movements with greater freedom). Choupo-Mouting was a more fixed 9 and Davies and Mazraoui, the full-backs, were very involved in building the game and attacked both through the middle and the flanks. However, despite a deceptive first glance, this team was anything but positional.

It was a Bayern team that was more spread out across the pitch, much more vertical and that explored width and external lanes to speed up the plays. However, the principles of the game were in no way reminiscent of that of a positional team. The game through the flanks, very present in this team, was not explored from wingers fixed in space; quite the opposite, Bayern often sought to empty the wings by retreating or dragging its players to central lanes so that they could infiltrate the empty spaces and attack the flanks with more depth and verticality. But the most important thing of all was that the external play didn’t come at the expense of internal play; in fact, it came to enhance the plays in central lanes, the true jewel of that team. In the central lanes, all the relationist principles of freedom of movement, of approaching, of pass and move and of moving higher up the pitch and creating empty spaces based on the players’ movements were still there, untouched. In the best German style, the plays on the central lane of that Bayern were frenetic, restless, role-driven, relationists, full of grooves and movements that broke with a positional order, seeking, based on these principles, to build plays through the middle to, in the final third, accelerate through the wings. Players had the freedom to move through long spaces, leave their initial positions, tear diagonals that crossed the field and, in short, make the team advance based on their individual movements, always based on the principle of emptying spaces to infiltrate them and give more dynamism and depth to the plays. Bayern was not organized by offensive zones or well-defined positional lines, despite a misleading first look. It was a team deeply rooted in relationist ideas, such as diagonals, “ladders” (staggering players vertically/diagonally, placing one at each height, always around the ball area, so that the team gains meters vertically in a more natural), empty spaces and player movements as an organizing principle of the offensive structure. It was, without a doubt, a deeply authorial team with strong cultural traits that made any fan of the 1970s German football proud.

The Sky over Berlin

The more positional style at Hoffenheim, the beginning of a more relationist and Germanic approach without abandoning positional principles at RB Leipzig, a more rigid and automated style at first at Bayern, the change to an orthodox, extreme relationist and role-driven approach in a subsequent moment, a period with stronger links to his Germanic cultural roots while still at Bayern and an end to his time in Bavaria very marked by rigid and automated positional football: all of this represents the identity crisis that Nagelsmann is going through..

In the other corner, however, Germany is also experiencing its own identity crisis. After years of trying to shape its game towards a more defined style of gegenpressing and ultra-vertical counterattacks “Rangnick style” in the first decade of the 21st century (a process that led Germany to a World Cup title in 2014), German football began to get upset with some aspects of this style. Overly unpredictable matches and an inability to put that game into practice against teams that sunk down in their defense and refused to hold possession were the first signs that Germany needed to change, and the answer seemed obvious.

The first half of the 2010s was marked by Pep Guardiola’s Barcelona and Bayern sides. And it was precisely at Bayern that Guardiola began to transform his Juego de Posición into a very well-defined and elaborate method, mechanizing principles that were easier to reproduce and replicate to accelerate the circulation of the ball and better fix the players in space. It was an aesthetically pleasing game for many and allowed absurd control over every situation in the game, something that Germany craved, even if it came at the cost of many players’ individuality and went against the country’s entire football culture.

Germany turned a blind eye to this and embraced the Juego de Posición. Slowly, names from the more traditional school of gegenpressing, such as Ralf Rangnick, were left aside and passed over by coaches better versed in the school of the Juego de Posición, such as Thomas Tuchel. Although some German coaches sought another path by mixing the gegenpressing school with the more traditional relationist German game, such as Klopp and Roger Schmidt, the majority followed Tuchel’s “editorial line”, buying an idea of modern, more complex and more advanced football. This process gained its place in the youth categories, and the formation of not only coaches, but also players began to be greatly affected by this. Players more focused on the Juego de Posición began to emerge, very capable of moving through short spaces, well-versed in two-touch play, ultra-specialized, with enough technical refinement to participate in a few touches, and slowly the most traditional philosophy of the German game was lost. After two consecutive eliminations in the group stage of the World Cup, both very marked by ultra-offensive teams, but not effective enough in attack and very fragile in defense, some timid but relevant voices (including some within the DFB and Flick himself) began to complain about a generation that was as talented as it was unbalanced. Germany no longer has a reliable number 9, something so traditional in the country’s football history (Gerd Müller, Rummenigge, Klinsmann, Klose, Podolski etc.). There are no reliable full-backs, high-level centre-backs and more defensively sound midfielders. There is a lot of talent in the midfield with Kimmich, Gundogan, Sané, Thomas Müller, Musiala, Wirtz, Havertz, etc., but few typically German players, versed in the game of transitions, vertical and relationnist, who performed long movements across the pitch and created empty spaces from their movements. Except for Kimmich, Musiala and Wirtz (in part), most of Germany’s best players were versed in and/or performed their best in positional systems which, although there is nothing inherently wrong with it, appears to be a huge counterculture in Germany. This entire identity crisis led to Flick’s dismissal, the first dismissal of a coach from the main Men’s National Team in the country’s history.

Returning to Nagelsmann, he has a lot to sort out. Perhaps, because he is still a very young coach, he has many mannerisms and addictions to overcome, such as, for example, his excessive obsession with controlling all the game situations and an almost anxious restlessness in making tactical tweak after tactical tweak when things are not going the way he envisioned. His young age and still limited experience at the highest level of football ended up enhancing these mannerisms and undermining Nagelsmann’s trust in his players when he found himself in higher pressure scenarios at Bayern Munich, for example, and ended up preferring to have more control of different situations of the game when assembling a mechanized and easily reproducible team and not one that gives enough freedom and responsibility to the players on the pitch so that they create spaces and advantages based on their own movements. However, at the core of his football philosophy, there is a very unique and rare trait to find in today’s football based on trust towards his players, something very well represented when he saw that the rigid positional structure had not worked at Bayern and decided to listen to his players and change it. Perhaps there was a lack of confidence to maintain this in moments of difficulty, but the idea, the philosophy of listening to your players and adjusting the tactical system to one that accommodates them in the best way is still there.

“I give my players patterns that apply to every basic structure and every phase of play. It’s important that my players put the principles we have into practice on the pitch at the weekend. And then switch them to suit the respective opponent. This makes us less predictable”, said Nagelsmann on his philosophy. This summarizes what is most interesting about the young coach: he prefers to instruct his players in basic principles, adapting and adjusting the squad’s profile to different situations, and then trusting them so that, in the game, they can apply and adapt those principles according to the scenario. Perhaps, with more confidence in himself and his players, Nagelsmann can build a more complex game with greater freedom. Furthermore, he is a very rich, very intelligent coach who carries several legacies with him. He inherits the culture of Juego de Posición for having always admired Guardiola and for having trained as a coach under Tuchel, but he also inherits the German football culture, based on transitions and relationist, vertical play, and also has traces of a more Danubian relationist game, focused more on clustering players to build plays slower from central areas. His mission now is to fight for all these heritages to truly be his, as they exist, are there and will be decisive for Nagelsmann’s development as a coach, but he cannot be held hostage by them. If he’s confused, well, Germany is even more confused; and if each one continues in their own confusion, Nagelsmann and the German National Team will be a marriage doomed to failure. He cannot copy the Juego de Posición, the Germanic game or the classical relationist game because someone said he should; he needs to understand each one of them, the relationship he has created with them and then find himself in the middle of it all. Fighting not to be a puppet of a culture, but absorbing them all, digesting them to their core, interpreting them and, finally, understanding who he really is. Struggling to make truly his own what he inherited from others is the main drama of Nagelsmann’s career so far.